What COP15’s Global Biodiversity Framework will mean here in Canada

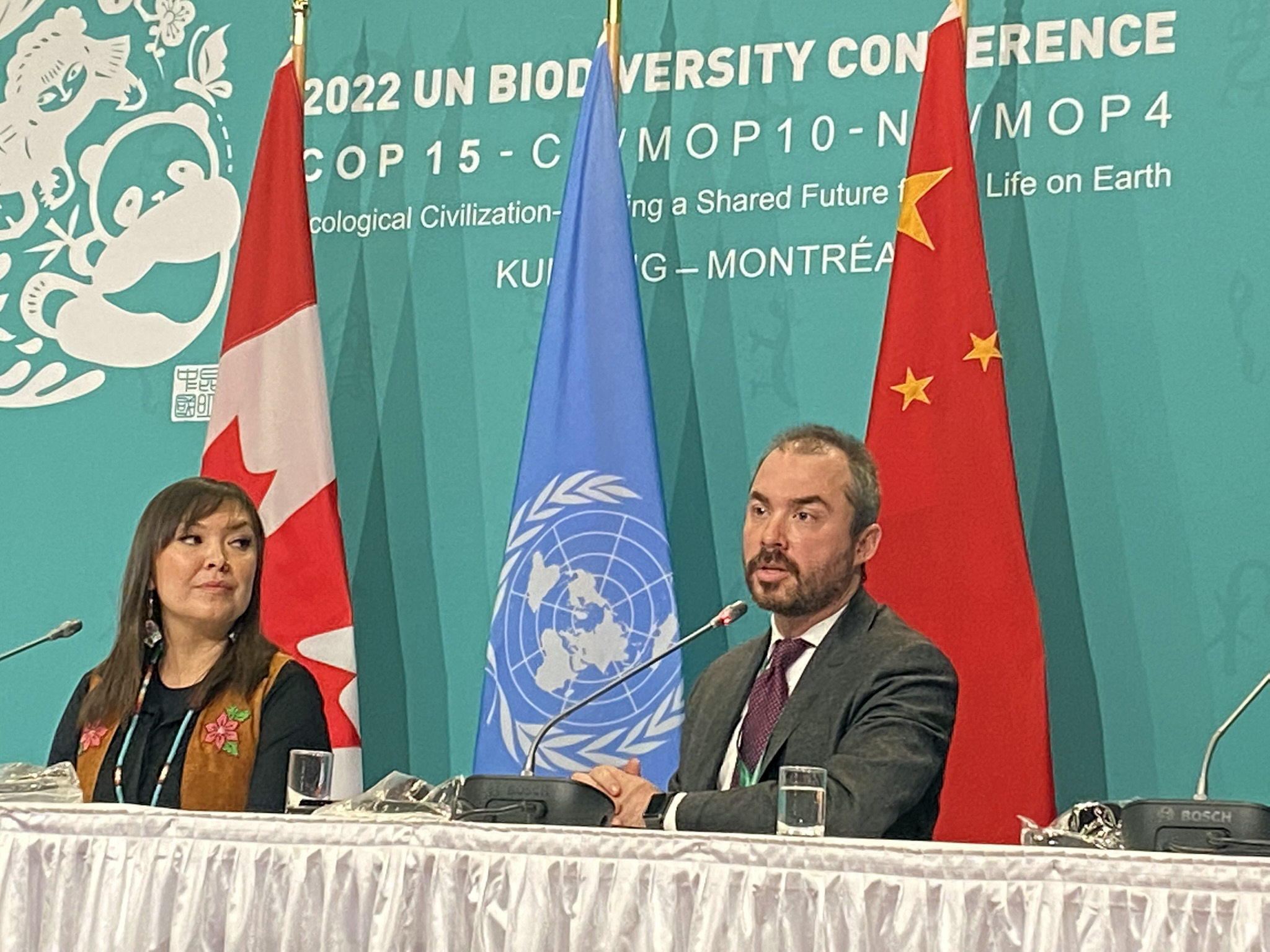

During a dramatic climax to December’s UN COP15 biodiversity summit, nearly 200 countries adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). Containing four overarching goals and 23 specific targets, the new agreement aims to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030, setting the stage for a 2050 where “biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used.”

Of course, reaching an agreement is only the first step of a very complicated puzzle.

As host country for the meeting — it was relocated here from China due to COVID concerns — Canada took centre-stage in terms of moving the global community forward, including getting the 30×30 goal of protecting 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030 into the final deal. Hopefully, this sets Canada on the path toward actively pursuing national policies and programs to effectively implement these ambitious goals.

But the last time world leaders agreed to a global plan for biodiversity — in 2010, when COP10 in Japan produced the Aichi Targets — they failed to fully meet any of them by decade’s end. So, how do we ensure that this time we actually reach the targets outlined in the GBF? How do we build momentum and choose the right steps to protect existing biodiversity while restoring habitats that we’ve already lost or damaged?

The problem (and opportunity) of implementation

The Government of Canada must now develop a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), which is a way for them to be accountable to the global community. It’s a moment to review current biodiversity-related policies so it can identify and fill gaps — for example, Canada has protected just over 13 per cent of its lands and waters so far. Importantly, the NBSAP can arguably be even more ambitious than the COP targets, which should be considered the floor and not the ceiling.

With only seven years left to create a clear path to protect per cent by 2030, as well as ensuring that 30 per cent of degraded are under effective restoration (which does not yet exist as an official domestic target).

In Canada, we’ve already heard lots of commitment from the federal government on how it plans to bring this multilateral agreement back home. But we also must recognize the roles the provinces and territories play, as they’ll need to step up with their own biodiversity programs and policies, as well as Indigenous nations who have expressed commitments to conservation of their jurisdictions.

And as we examined in our recent Beyond Targets report, it’s not just about quantity but quality — choosing areas that prioritize nature-based solutions by protecting both biodiversity and carbon stores, as well as those that prioritize Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas.

Indigenous-led conservation is crucial

COP15 saw a crescendo in terms of focus on Indigenous-led conservation to achieve these ambitions, including Canadian funding announcements for Guardians programs and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas such as the feasibility study for the Seal River Watershed and a Project Finance for Permanence investment to support Mushkegowuk conservation work in the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands.

The text of the agreement itself ensures the actions we take for biodiversity respect Indigenous rights and title. And by recognizing and supporting Indigenous knowledge, perspectives, cultures and roles, we can change our relationship with nature for the better.

Many elements of the GBF already align with WWF-Canada’s Regenerate Canada strategic plan, and it’s an opportunity to advance the impact of our work over the coming decade. There’s commitment to protection and restoration as well as supporting stewardship by Indigenous and local communities.

We’re also happy to see the explicit mention of nature-based solutions in the text of the GBF. It means the international community has recognized the link between biodiversity and climate change — this is an especially big deal in Canada where we have 327 billion tonnes of ecosystem carbon currently stored in nature.

Finally, we’ll need to see some sort of Accountability Act from the government that will bring in formal legislation to report on the progress that we make to the international commitments agreed to in the GBF.

In whatever way we decide to move forward, the key will be to use the momentum from this agreement in Montreal to ensure that implementation starts right now.

This article originally appeared in our monthly newsletter, Fieldnotes. Click here to subscribe to future issues.