Mushkegowuk Council’s Vern Cheechoo on peatlands, climate change and the ‘Ring of Fire’

To help inform their stewardship decisions, the Mushkegowuk Council, which represents seven First Nations communities in northern Ontario, is working with WWF-Canada and McMaster University’s Remote Sensing Lab to “ground-truth” the carbon mapping research launched at COP26.

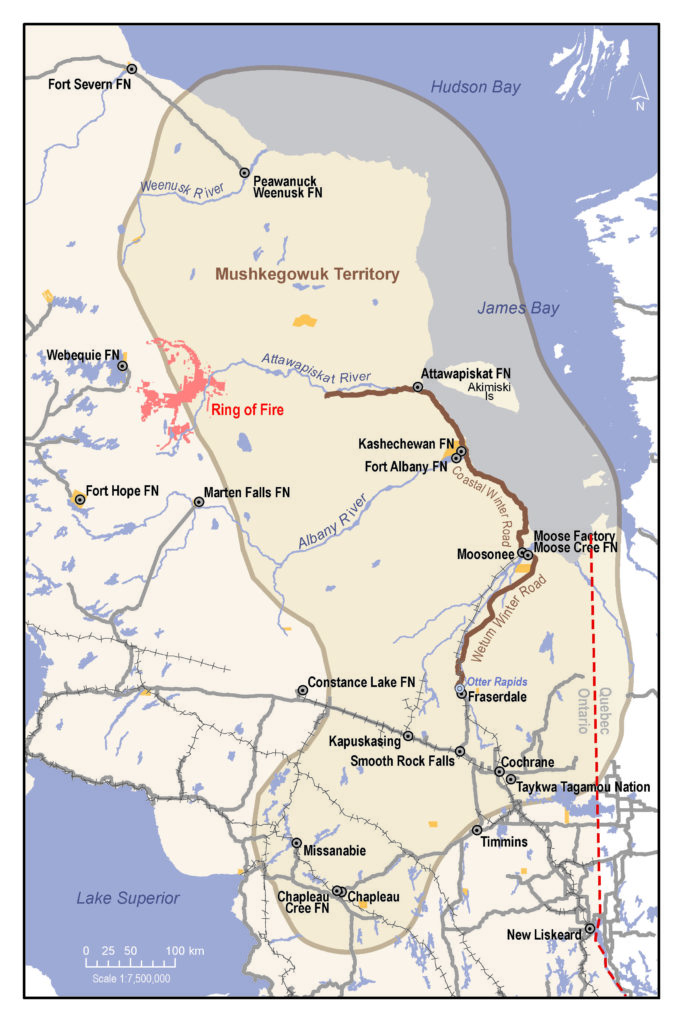

So we sat down with Vern Cheechoo, the Council’s Lands & Resources director, to find about more about their territorial peatlands and community-led carbon field sampling as well as rising regional threats from climate change and the planned Ring of Fire mining development.

The Hudson and James Bay Lowlands are a globally significant centre of carbon storage. What else can you tell us about this part of Mushkegowuk territory?

We live in a very unique region of the world. Its size is immense — the largest wetlands in North America, which house the second largest carbon sink in the world. They say it’s worth approximately $700 billion a year in [ecosystem] services, and that means recharging aquifers, providing habitats for animals of many species, etc. It’s a very important bird staging area. Nearly 400 species of birds come to have their young and, in the fall, 3 to 5 billion birds migrate back down to the southern regions, all the way to South America!

What does this mean for Omeshkego people?

We have lived in this region since time immemorial, as we say, living off this region for what it provides us — the animals, the fish and so forth. We say that the Creator gave us everything that we needed to live a healthy, vibrant lifestyle.

How are things changing?

Climate change is impacting the region. We’re experiencing more winter rains. The winter road system is a shorter season, making it difficult for communities to get supplies. It’s impacting our food security and making it more difficult for people to get to their hunting areas.

The people in the region know how to read ice and snow within the wetlands when we travel and it’s becoming more treacherous because the snow has changed, the ice conditions have changed.

Then we have a large influx of water in the springtime and, in the summer months, the water levels are right down and people can’t access their territories up the river and gather their food because it’s so shallow.

How is the Council working to protect and steward this culturally important place?

The Elders have referred to this area as the Breathing Lands of Mother Earth because of what it does for the world in sequestering large amounts of carbon and cooling the Earth.

The best thing you can do with the wetlands is to leave it alone and allow it to do what it does. It’s still doing its job, and what we’re trying to do at Mushkegowuk is bring attention because, in large part, it has been ignored.

Climate change is a big issue globally, but no one was talking about the significant carbon sink that we have in our region. So, we have different projects that we’re following up on, like the WWF-Canada carbon mapping project.

Tell us about your work on monitoring and measuring carbon?

Mushkegowuk Council is quite happy to be part of this sampling project, collecting the peatland cores to measure carbon.

We’ve had great success in this first year, building capacity within the Council and a monitoring team which involves different individuals from each community. We’d like to continue monitoring year after year to highlight changes and find out how to protect and conserve this region.

Why have the Mushkegowuk Chiefs called for a moratorium on development on your territory?

Because our region’s wetlands could be impacted from potential development that’s to happen just west of here called the Ring of Fire. They’re talking 150 to 200 years of mining and the size is, roughly, 10 times bigger than the De Beers mine along the Attawapiskat River. [The open-pit Victor diamond mine, which shuttered in 2019, had an impact area of 5,000 hectares.)

We’re calling for a proper protection plan in place for the wetlands from cumulative impacts that could happen — not only downstream but down muskeg because there are streams that run underneath that feed the rivers and also into James Bay, where we’re working to create a National Marine Conservation Area. We look at it as one ecosystem.

And can you explain your concerns about regional assessment under way for the Ring of Fire?

The federal government did announce one and we’ve been meeting with them regularly. Our push is to have co- governance and to be directly involved in this process. As we’re the ones that could be impacted as the communities within the vicinity of the Ring of Fire, our community should sit at the table in assessing what potential cumulative impacts could happen.

Our request to be involved has been refused by the Impact Assessment Agency, they say that will not happen. They will establish a committee of experts, people that will listen to the concerns of all of the people involved, all the stakeholders and the First Nations in the region.

We’re having to explain ourselves rather than being part of the decision-making, so we’re disappointed. We are the ones that have the connection to the land. And we feel that we are being severed from that and someone else is going to make the decision of how it’s going to impact our region.