WWF-Canada advocates for the creation of more Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and Inuit Protected and Managed Areas where Indigenous governments and community organizations have the primary role in protecting and conserving ecosystems through Indigenous laws, governance and knowledge systems. We partner with Indigenous communities and groups — from sea to sea to sea — to advocate for common concerns and achieve shared goals .

In the west, we continue to support the Katzie First Nation’s salmon habitat restoration work along the Upper Pitt River Watershed and marine protection efforts for humpback, fin and killer whales with Gitga’at First Nation in the waters alongside the Great Bear Rainforest. We’ve also developed a new partnership with the Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society in B.C.’s central interior to help restore their traditional territory to precolonial conditions, beginning with 192,000 hectares badly damaged by wildfires. On the East Coast, WWF-Canada is supporting Wolastoqiyik efforts to create a management framework for the threatened Wolastoq (Saint John River) watershed. This builds on the recently released Priority Threat Management report, which identified strategies and actions to recover over 40 species at risk in the watershed over the next 25 years.

In the Hudson and James Bay Lowlands, we’re supporting efforts by the Mushkegowuk Council to conserve and steward their marine and terrestrial territories. This includes mapping peatland carbon stocks and training community members in carbon monitoring, protecting biodiversity by supporting a feasibility study for a National Marine Conservation Area and assisting with regional environmental assessments.

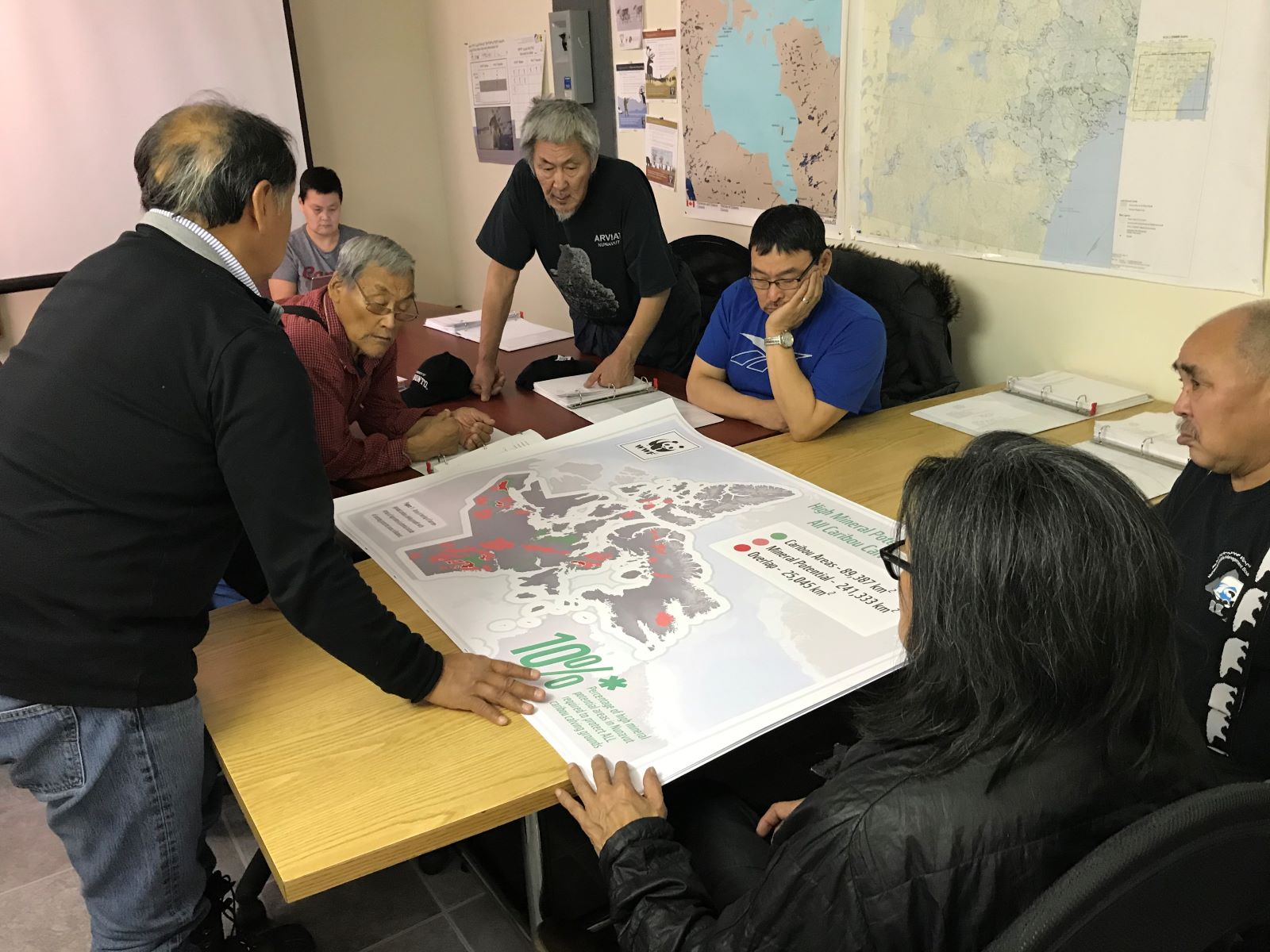

We’ve also supported communities in their submissions to the draft Nunavut Land Use Planning process on issues like protection of caribou calving grounds, helped facilitate community testimony at hearings over Baffinland’s proposed Mary River Mine expansion, and are partnering with the Nunavut communities of Kinngait, Sanikiluaq and Arviat in the development of small-scale community-based commercial fisheries as sustainable, low-impact and Inuit-owned alternatives to industries like mining or oil and gas.

Our Arctic Species Conservation Fund, currently in its sixth season, supports high-quality stewardship and research initiatives such as a community-led polar bear survey in Coral Harbour. And we are supporting the community of Taloyoak in their efforts to create an 85,769 sq. kilometre Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area.

The Last Ice Area, a region above Nunavut where climate scientists project sea ice will persist the longest, is an example of how traditional knowledge and scientific research can work together to help nature and people. WWF’s initial data provided a foundation for the Qikiqtani Inuit Association to negotiate the creation of Tuvaijuittuq. One of the world’s largest marine protected areas, this climate refuge for ice-dependent species also economically benefits local communities.

In the past, conservation practices often ignored the power of Indigenous knowledge, guidance and experience to the detriment of Indigenous peoples and our planet. Conservation with justice, equity and inclusion is essential to protect the nature we all rely upon.