Explaining the 73 per cent decline in global wildlife populations (and what we can do about it)

A 73 per cent decline, on average, in monitored mammal, bird, fish, amphibian and reptile populations around the world over the past 50 years — that’s what WWF’s Living Planet Report (LPR), the 15th edition of our flagship state-of-wildlife analysis, recently revealed.

Called “catastrophic” by WWF International’s Director General, Dr. Kirsten Schuijt, these jarring trends were found by analyzing 35,000 populations of more than 5,000 vertebrate species from 1970 to 2020. (A population is a group of the same species living in the same place and the LPR does not analyze plants or invertebrates such as insects, spiders and shellfish.)

Digging deeper

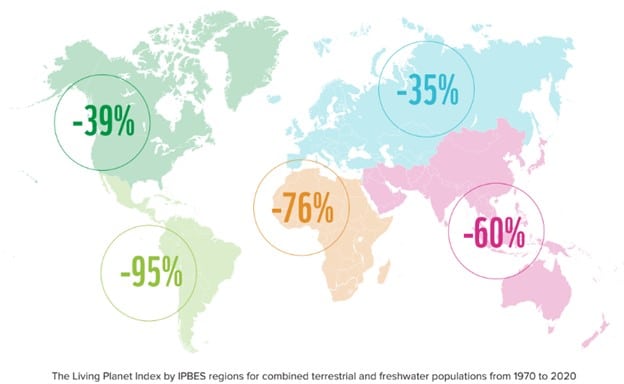

Of course, a global average doesn’t tell us regional trends. The report also shows that these declines are most significant in Latin America and the Caribbean region, with populations declining an average of 95 per cent, while we found a 76 per cent decline in Africa, 60 per cent in Asia and the Pacific, 39 per cent in North America and a 35 per cent decline in Europe and Central Asia.

When we group species together based on habitats, freshwater species showed an alarming 85 per cent average decline while terrestrial and marine populations didn’t fare much better, declining by 69 and 56 per cent, respectively.

What is causing this?

The report shows several drivers of species population loss. There’s the impact of illegal poaching, as with the critically endangered African forest elephant’s decline in Gabon and Cameroon. And there’s the increasingly indisputable connection between wildlife loss and climate change.

The critically endangered hawksbill turtle, found around Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, saw a 57 per cent decline driven largely by climate impacts like coral bleaching while the Amazon’s pink river dolphin has experienced a 65 per cent decline as its habitat heats up — as many as 330 dolphins died in 2023 alone due to extreme heat and drought-lowered water levels.

Chinook salmon in California’s Sacramento River have seen an 88 per cent decline due partly to warmer river temperatures reducing egg survival for this cold-water-spawning species, an issue also affecting Canada’s Pacific salmon population declines, like Okanagan chinook and Fraser sockeye.

But the 2024 LPR analysis, alongside other reports like the UN’s IPBES Global Assessment report, shows that the biggest driver is habitat loss and degradation, which itself is driven by factors ranging from human activities like logging, mining and agriculture to climate impacts like worsening floods and fires.

The recent State of Canada’s Birds report from Birds Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada, using the same Living Planet Index as LPR, showed some groups of birds species declining drastically alongside habitat loss, such as grassland birds, which have declined by an average of 67 per cent. Meanwhile, not coincidentally, the 2024 WWF Plowprint Report showed more than 190,000 hectares of native prairie grasslands in the Northern Great Plains were converted to croplands and perennial cover in 2022.

Meanwhile, 6.3 million hectares of forest, an area the size of Ireland, was lost last year to deforestation, according to the global Forest Declaration Assessment report. Nearly half that number was from tropical forests, but losses like this impact forest-dwelling species populations around the world, from woodland caribou in Canada to Queensland koalas in Australia.

What can we do?

The situation may seem dire, but we know what we need to do to reverse the decline of biodiversity. At the international level, we need to implement the ambitious goals and targets that were set forward in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) agreed to by global leaders in at the COP15 biodiversity summit in late-2022.

These goals include protecting 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030 to avoid the destruction and degradation of important natural areas. Canada has a unique global responsibility to protect large remaining intact ecosystems — these include primary forests in our boreal zone and large swaths of peatlands, such as those found in the Hudson-James Bay Lowlands, which store billions of tonnes of irrecoverable ecosystem carbon that has accumulated over thousands of years.

We also know that broad-scale restoration of converted and degraded lands is necessary to see the recovery of species at risk of extinction — Canada and other nations committed to restoration of 30 per cent of degraded lands underway by 2030 — and WWF-Canada has identified 3.9 million hectares of land that, if restored, would provide high value for both biodiversity and carbon storage.

We also already have proven examples of conservation actions leading to species recovery. After the systematic banning and removal of DDT, the then-endangered peregrine falcon came back in such numbers over recent decades that the majority of populations are no longer listed as at-risk.

Many waterfowl and wetland birds have also shown significant recovery in that period of time — species like wood duck, hooded merganser and sandhill cranes have seen populations increase in Canada in response to conservation interventions.

These reports show that conservation works

The issue is that the resources to achieve the pace and scale needed to meet this challenge are far beyond what is currently being allocated — and that roadblock is standing in the way of the world reaching its GBF goals.

To date, we’ve only seen about one third of countries that committed to the GBF deliver their mandated actions plans (NBSAPs) outlining how they’ll reach their goals and targets and while Canada is thankfully among them, we’ll need to see much more from the international community if we’re to actually halt and reverse wildlife loss by 2030.

That is what will make the coming days in Cali, Colombia, where world leaders are meeting at COP16 until Nov. 1, 2024, so crucial to converting these international commitments into on-the-ground action.