Snow leopards reveal mysteries of their life in Nepal’s Himalayas

When a snow leopard was collared with GPS technology for the first time in Nepal back in 2013, it was a breakthrough moment for the conservation of this under-studied big cat.

Dr. Rinjan Shrestha, WWF-Canada’s lead specialist for Asian big cats, was part of that historic expedition (read his first-hand account here) and subsequent long-term study tracking the movements of multiple snow leopards through the Himalayas. The findings were published earlier this year, shedding light on the secretive lives of this elusive feline.

I still vividly remember the chilly morning of November 25, 2013. My team and I were resting at camp when we received a transmitter message around 5 a.m. alerting us that a foothold trap had been triggered. We quietly hiked uphill at 4,500 metres above sea level in the Eastern Himalayas.

It turned out to be a male snow leopard, who we named Ghanjenjwenga and fitted with a GPS-equipped collar, a first in Nepal. Over the next four years, we collared three more snow leopards, Omi Khangri, Lapchhemba and Yalung.

Thanks to the satellites roaming up in the sky, we were able to remotely track them as they travelled through rugged mountain cliffs and glaciers that are often inaccessible to humans. In doing so, these snow leopards were helping us understand their secretive world and teaching us how to better protect them.

This breakthrough study, recently published by a scientific journal, revealed findings that are both surprising and deeply motivating for conservationists.

Snow leopards need more space than expected

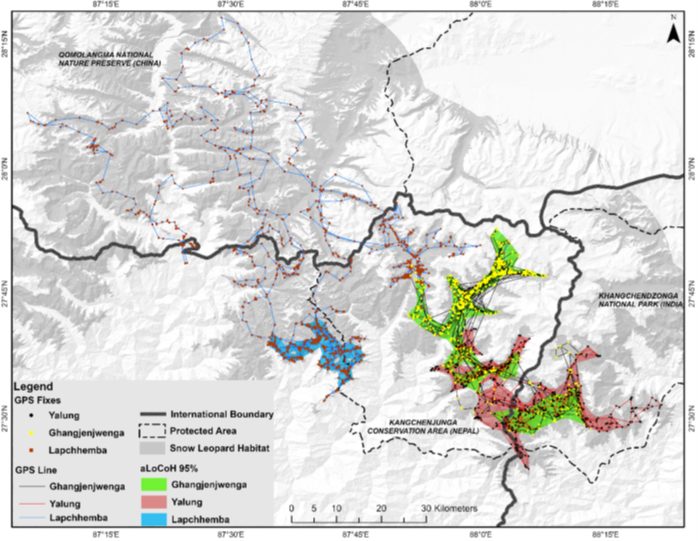

Perhaps the most striking finding is the amount of space snow leopards need. Their home ranges — the areas where each snow leopard hunts, mates and rests — are six to 97 times larger than previous estimates! One male snow leopard covered more than 300 square kilometres while two of the females averaged 200 square kilometres.

This tell us that the isolated protected areas alone are not enough to save snow leopards: they need vast, connected and undisturbed landscapes to survive.

They take frequent international trips

The study also confirmed that snow leopard habitats cross international borders. The cats we collared in Nepal spent up to a third of their time in neighbouring India and China. Notably, almost half of Yalung’s range overlapped with India’s Khangchendzonga National Park.

This reinforces the fact that conserving snow leopards is not just a job for one country. Snow leopards don’t recognize human maps, so it’s vital that Nepal, India and China work together to ensure the safety of these cats as they roam freely across their shared mountain landscapes.

Life up on the roof of the world

We also recorded a snow leopard at 5,848 metres above sea level, which is the highest altitude ever documented for this species. These cats seem to prefer to dwelling between 4,000 and 5,000 metres, favouring rocky valleys and alpine grasslands, while avoiding dense forests and icy cliffs.

What does this mean for snow leopard conservation?

Snow leopards are known as the guardians of high Asia because, as apex predators, they help keep vital ecosystems in balance. By protecting snow leopard habitat, we also protect the rivers that flow down from their mountain habitat and these “water towers of Asia” ensure the lives and livelihoods of over 300 million people.

Sadly, snow leopards are facing unprecedented challenges such as habitat loss, poaching, and conflict with herders.

I’m hopeful that this study will provide conservation practitioners with much-needed information about the habitats and conditions snow leopards need to thrive. Our findings are already shaping Nepal’s next Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan, which emphasizes cross-border cooperation and landscape-level conservation to ensure the survival of snow leopards — today, and into the future.