Polar Bears from Space

Co-Written by: Seth Stapleton, Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, University of Minnesota and Michelle LaRue, Conservation Biology Graduate Program, University of Minnesota

One of the central challenges facing polar bear research is that bears live in an incredibly vast and remote region, and conducting research there is very difficult. The entire Arctic is almost four times the size of the continental United States and is mostly inaccessible, often with inclement weather. Gathering information about how many bears live in a given area and how they are distributed across the landscape is critical for management, but it’s also time-consuming, dangerous, and expensive. And sometimes, research is altogether impossible because sites are simply too difficult to access.

A traditional polar bear research program involves working from helicopters and searching across huge expanses of sea ice or land for bears. Some studies primarily record data about where bears are spotted on the landscape, whereas others involve capture: bears are sedated, tags are applied to identify them in the future, and samples are collected to learn about age, health, and diet, among other things. Although these studies provide detailed and valuable information, such intensive surveys can take years to complete, can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, can be disruptive to the animals captured, and simply aren’t feasible everywhere.

However, to better understand how the rapidly changing Arctic is impacting polar bears and how best to manage their populations, scientists and decision-makers need even more frequent information from across the Arctic.

This growing need for information, combined with research limitations, inspired a number of partners to come together to try something new: using satellite imagery to count bears.

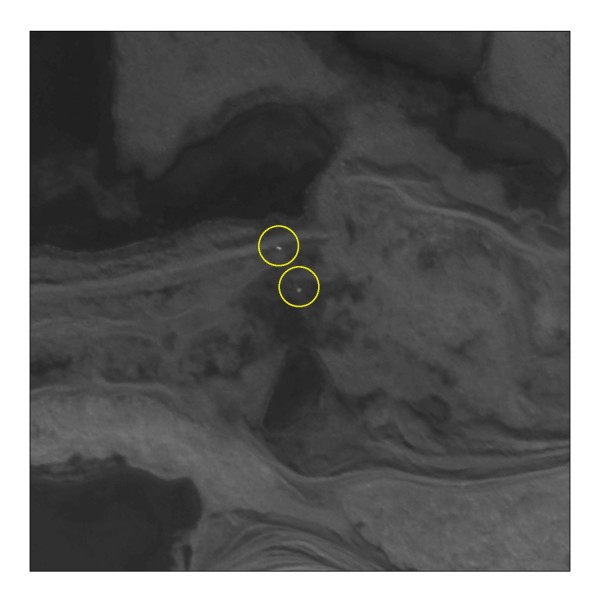

We took the first step in August and September, 2012, by collecting imagery of Rowley Island in Foxe Basin, Nunavut, Canada. We chose this location for its flat terrain and high densities of bears during late summer (when there’s no snow on the ground), when conditions were ideal for the pilot project. We then spent hours reviewing the images to identify polar bears, and we checked our counts against an aerial survey, which involved flying over the region and counting bears from a helicopter.

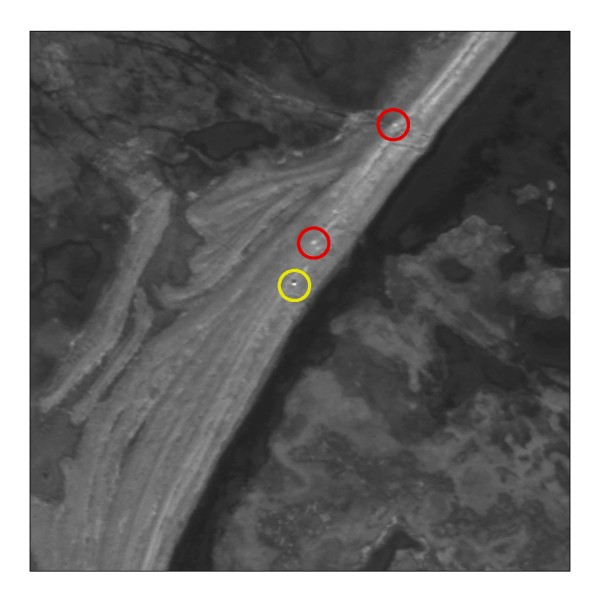

The initial project was a success – our results were consistent with the aerial survey, and our validation process suggests that we can accurately identify polar bears with satellite imagery. So, we have moved on to phase two. We’re now trying to automate the process to eliminate those dozens of hours of image review, making this technology more practical on a larger scale. We’re also testing how well satellite imagery works in less ideal conditions. For this aspect, we chose sites including Baffin and Bylot Islands, which have more rugged terrain and cover much larger areas. While the project is still underway, early results are promising: by selecting for specific attributes of the images, we are automatically differentiating polar bears from the rest of the landscape. We hope that expanding this method will prove valuable in future research, with lower costs and no risk to human (or bear) safety.

Using satellite imagery as a monitoring tool also may provide a new way to engage communities. Given their familiarity with the land and wildlife, many northerners are well-positioned to review satellite imagery and identify wildlife. This would also empower communities with regular information about polar bear numbers and distribution in their regions.

Phase 2 of this project is supported by funds from the Arctic Home campaign: give to WWF’s Arctic efforts today and Coca-Cola® will match your donation dollar-for-dollar until March 15, 2014, to a maximum of $1 million USD (Canada and U.S. only).