Fieldnotes: We ❤ Polar Bears

How we’re helping the world’s (literally) coolest apex predator

No species is more emblematic of the High Arctic than the polar bear. Known as Nanuq in the Inuit language Inuktitut and Ursus maritimus in science-speak — meaning “sea bear” in Latin — this majestic animal is one of the planet’s greatest predators.

It’s also the biggest bear around and the largest land carnivore, clocking in at as much as 800 kg and up to three metres in length. Unlike their other ursine cousins, polar bears are marine mammals (just like whales)! In fact, they can swim for days at a time and reach speeds of up to 10 km/h thanks to specially adapted paws and hind legs.

Southerners may think of polar bears prowling for food on land, but they actually capture their ringed seal meals — which they can, amazingly, smell from a kilometer away — out on sea ice.

This is also where the danger to polar bears lies: the climate crisis is heating the Arctic at three times the global average, increasingly reducing the sea ice habitat where they mate, raise cubs and hunt. This is of particular concern in Canada, which is home to two thirds of the world’s estimated 26,000 polar bears, which are divided into 19 subpopulations.

While many of these are currently stable, a few of the more southern subpopulations are declining and bears are showing worrying signs in terms of body condition and cub survival. In fact, just this week a new study in Baffin Bay linked declining sea ice to skinnier bears and less cubs being born. Other studies have projected the effects of climate change will cause a 30 per cent decline in the global population by 2050.

To help prevent this, WWF-Canada’s conservation efforts are multifaceted. We support combining scientific research and Inuit knowledge to study the health, status and management of their subpopulations. We also work to protect their most vital habitats, including areas where female polar bears give birth and current and future marine protected areas like Tallurutiup Imanga and Tuvaijuittuq, a.k.a. the Last Ice Area.

We also work with local communities on reducing human-polar bear conflict. This has become an increasing concern, especially in the western Hudson Bay region of Nunavut, where migrating bears spend more time on land in search of food, often wandering into communities and threatening the safety of people and sled dogs.

We have multiple projects researching the drivers of problem polar bears and this past year we started a community-based initiative in Whale Cove, Nunavut to manage attractants like garbage dumps and human food storage as well as employing a bear monitor to keep the community safe.

Polar bears have inhabited the Arctic since time immemorial. Even in the face of unprecedented change to their habitat, if we work together, we can help safeguard their far north future, too.

Polar Bear Walk (and Talk)

When Sean Hutton was seven years old, he decided to help his favourite apex predator. Inspired by the thousands of kilometres that polar bears trek across sea ice every year — and worried about the impact of that ice shrinking due to climate change — he founded the now-annual Polar Bear Walk to help WWF-Canada fundraise to safeguard the species.

What began in Hutton’s Guelph, ON, hometown in 2013 has since spread across the country with thousands of kids celebrating International Polar Bear Day by participating in their own walks with friends, family and schoolmates while raising over $37,000 for our work protecting the Arctic and fighting climate change.

The cool thing about it is that anyone can host a Polar Bear Walk! Click here to find out how to help your kids or students organize their own.

Oh, and there are rewards for fundraising, too, including a chance to win a panda visit and a Q&A session with our resident polar-bear expert, Brandon Laforest (who explains more about polar bears below).

Q&A: Tracking down the Arctic’s iconic bear

The more we know about polar bears, the more we can do as the climate crisis starts melting the sea ice beneath their paws. Brandon Laforest, WWF-Canada’s senior specialist for Arctic species and ecosystems, tells us how technology is helping us help both bears and people.

What is satellite telemetry?

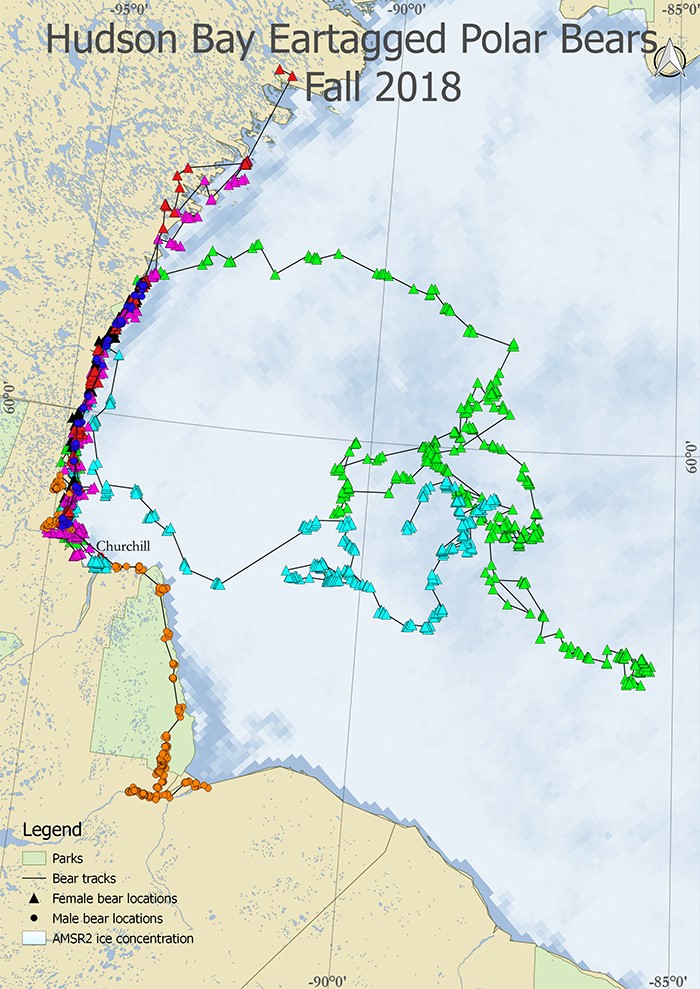

It means using satellites to track something on Earth. It’s one of the most used advancements in conservation technology as it allows wildlife tracking in real-time from the comfort of your office. For species with wide ranges, such as polar bears — they can cover over 5,000 km per year — this technology uses radio tags to track for long periods of times with minimal disturbance.

Why are we tracking polar bears?

For the past 20 years, the big push for polar bear telemetry has been to figure out the basic ecology of these animals. Where do they travel when they’re on ice? What dates do they leave and come back on shore? What are their home ranges? Comparing past and current travel routes and timing also allows us to better understand how the climate emergency affects polar bears at the individual and population level.

But a bigger issue evolving with polar bears right now is their interaction with people. As sea ice declines and bears spend more time on land, there’s been an increase in how often polar bears and people cross paths.

So, the shift in telemetry work now is trying to use this tracking system to potentially predict human-polar bear interactions, determine drivers of this conflict, and, more importantly, reduce it.

Tell us about the work WWF is doing with University of Alberta on this front.

The project focuses on polar bears in the Western Hudson Bay subpopulation that have caused conflicts with communities by placing a satellite-linked ear tag on the bear to track their movements once they’ve been released far away from Churchill, Manitoba.

Post-release tracking helps us understand whether these bears will “re-offend” in other communities and how they migrate farther north. To date, approximately 41 ear tags have been recovered from polar bears and new data analysis is underway to assess the biological and environmental factors affecting bear movements and conflict with humans.

Meet WWF-Canada’s VP Arctic

Jessica Park – Acting Vice President, Arctic

Jessica has been working with WWF for eight years. She oversees the implementation of WWF-Canada’s Arctic program and manages a team of Arctic professionals and specialists.

“I feel privileged to work with a team of dedicated individuals who care deeply about the wellbeing of the Arctic and the people who call this remarkable part of our country home. Beluga whales, polar bears and narwhals captured my imagination as a child. I want to ensure that these species exist for the next generations.”