How Canada’s shipping industry can reduce its climate change impacts

Marine shipping connects the world by supplying essential goods. But while boasting in some cases transportation’s lowest carbon footprint per tonne transported, the industry’s still-significant climate change impacts can no longer be ignored.

Canadian shipping alone contributed eight million tonnes of CO2 in 2019, according to our recent report, while global shipping accounts for three per cent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions — more than airplanes! — and is projected to see a 16 per cent increase between 2018 and 2030 if we don’t do anything about it now.

That’s why it made headlines when 19 countries, including Canada, came together at the recent COP26 climate conference to announce new “green shipping corridors,” shared maritime trade routes intended to accelerate zero-emission shipping.

But despite shipping finally warranting some goal setting from world leaders, Canada currently does not have any domestic marine shipping GHG or black carbon emissions reduction targets. Goals need to be backed up with targets, timelines, and regulations. Canada has largely failed to do this and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has done so very weakly and with a target that will not keep global warming below 1.5C.

(This fact was acknowledged when the Canadian Press broke a story this week that Canada “is considering an international proposal that would double the ambition of its greenhouse gas emissions targets from shipping,” setting a net-zero by 2050 target. But while evidence of progress, the article also notes that “the language in the resolution is non-binding, saying only that current targets are inadequate and net-zero is ‘essential.’”)

The real issue is that most ships currently burn heavy fuel oil (HFO), a dirty fuel which not only releases GHGs like carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, but also tiny dust particles called black carbon (or soot).

Black carbon accounts for one-fifth of shipping’s climate impact

This lesser-known HFO byproduct settles on Arctic sea ice, absorbing sunlight and converting it to heat, which vastly accelerates Arctic melt and increases atmospheric warming. It’s also toxic, contributing to heart and respiratory diseases in Arctic communities.

Black carbon has a global warming impact akin to methane, which is why the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has called for it to be reduced heavily to help achieve climate targets. Yet there are no global regulations from the International Maritime Organization to restrict it.

The closest is a weak proposed plan to ban HFO in the Arctic that doesn’t come into full effect until 2029 and has ample room for loopholes. The Arctic Council has created targets and timelines to reduce black carbon, However, there has been no follow-up by the federal government.

These weak and hazily applied regulations add to the pattern of ambiguity in the responsibility of federal and international authorities to reduce shipping pollution. For Canada to keep global warming under 1.5C, we need to achieve zero emissions by 2050 by reducing GHG and other emissions through economy-wide decarbonization, which includes necessary mandating of the shipping sector.

One way to do this is to more effectively apply emissions-reduction mechanisms like the proposed Clean Fuel Standard (CFS) and Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act specifically to Canada’s shipping industry, regulations which are not currently maximized to decarbonize the shipping sector at the rate that is needed.

While Canada may not regulate all ships that sail in Canadian waters, we can start here at home with domestic shipping (to and from Canadian ports), which was responsible for nearly 30 per cent of the sector’s CO2 emissions in 2019.

How clean is the Clean Fuel Standard?

The primary objective of the CFS is to increase clean fuel supply and investment in advanced technologies in all sectors that use fuels, to achieve at least 17.5 million tonnes of annual reductions in GHG emissions by 2030, through establishing a credit market where emitting parties can earn or buy credits. While the CFS could offer a potential pathway to transitioning off dirty fuels like HFO to cleaner fuels like hydrogen or ammonia, the draft regulation currently misses the boat.

In July 2021, just before releasing the proposed regulations, Canada quietly decided to exclude HFO from the scope of the CFS. As the final regulation has yet to be published, WWF-Canada and other environmental non-government organizations are pushing for the government to reverse this missed opportunity and incentivize a shift to cleaner shipping fuels instead.

On top of this, fuels sold for use in shipping vessels with international port destinations will not be included in the CFS as international shipping emissions are regulated by the IMO.

However, there is considerable critique around the IMO failing to implement effective climate regulations, providing a chance for Canada to step up by including stricter national policies.

How much does our future cost?

The Canadian carbon pricing system, under the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, was a huge first step for Canada. It has potential to successfully encourage clean shipping, especially given that it has a fuel charge for HFO, but strengthening is still needed. Part of the carbon pricing system is a regulatory charge on fossil fuel, which varies by province, but should at least meet the federal benchmark of $40 per tonne of emissions in 2021.

However, many jurisdictions (B.C., Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, P.E.I., Quebec, NWT) have their own version of a carbon pricing system, and the federal rule doesn’t require these provinces and territories to explicitly cover marine fuel, so some, such as N.L., have excluded it.

Notably, the carbon pricing will not be able to incentivize needed emission reductions for the shipping industry until the price on carbon is higher than the costs associated with mitigating carbon pollution. The Solomon Islands, Marshall Islands and Tonga called for a universal $100/tonne carbon price to be imposed on the shipping industry. The current price of carbon pollution in Canada, while helpful, will not drive the needed emissions reductions unless it explicitly includes marine fuels and ups the rate of annual increase, which is now just $15/tonne per year.

The way forward

The net effect of Canada’s regulations on the maritime industry is too weak to bring down emissions at the rate needed. The government needs to set more ambitious targets, like other countries have already done.

The European Union has made a legal commitment to become the first carbon-neutral continent with a target of 55 per cent reduction in emissions from 1990 levels by 2030 and no sectors are exempt. Shipping companies also pay for all carbon emitted from domestic port voyages, and half of their emissions from voyages to and from non-EU ports.

Ambitious shipping targets are also on the table in the U.S. where the Biden administration committed to work with countries at the IMO to achieve absolute zero emissions from shipping by 2050.

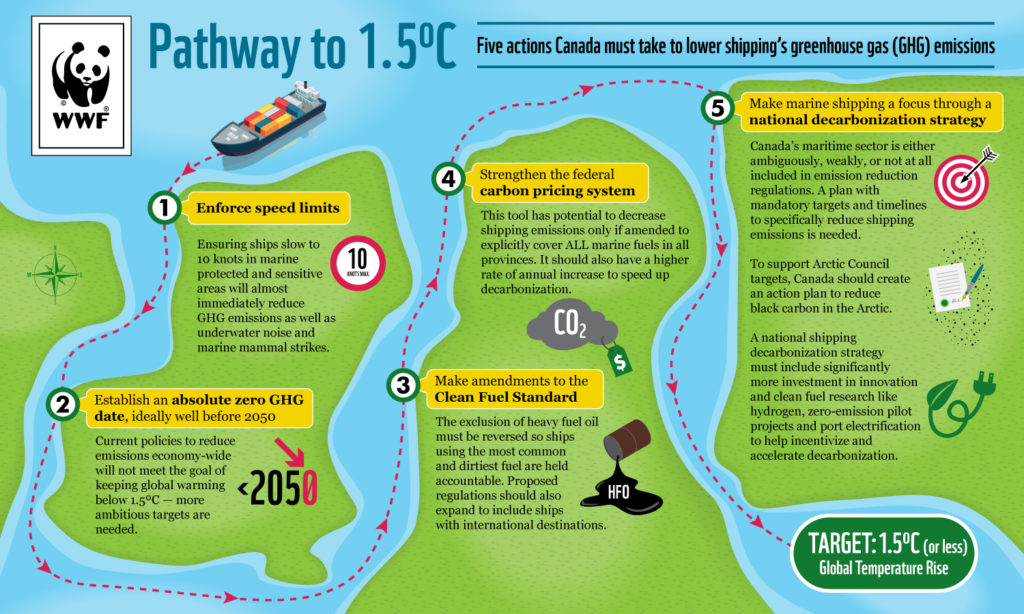

Put simply, shipping is a crucial part of the equation to reach our climate commitments. Now Canada must get to work reducing these emissions by enacting stringent regulations with clear application to shipping bolstered by targets and timelines, as shown below: