Forest for the trees: WWF-Canada’s year in conservation

Year in Review

2023 began with the promise of progress. The Global Biodiversity Framework had just been signed at COP15 in Montreal, setting humanity on a mission to protect and restore a third of planet before decade’s end — a goal that will halt and reverse wildlife loss while helping fight climate change.

An Environics survey we released last January showed Canadians are overwhelmingly behind this mission too: 77 per cent believe we’re at a crisis point and must act in the next 10 years to reverse biodiversity loss, and half of Canadians want the federal government to make its 30×30 target of protecting 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030 a top priority.

Then, of course, the rest of the year saw the country, and the world, beset by the nightmarish impacts of climate change — record-shattering wildfires, floods, superstorms and heatwaves — eventually ending with the near-failure of this month’s COP28 climate summit in Dubai after “phase out fossil fuels” was removed.

READ MORE: Power to the people @ COP28: UN climate summit makes progress

But the global uproar from concerned countries — and people like you — added enough pressure for the agreement to pass. As the summit pushed into an extra day, a still-historic pledge to “transition away” from fossil fuels, the first such reference in a climate agreement, put us back on the right path toward nature’s recovery.

But as we look back, 2023 was actually full of that promised progress. As WWF-Canada’s president and CEO Megan Leslie reminded us in our Annual Report, two steps forward, one step back is still one step forward.

And we took a lot of steps forward this year.

Indigenous Leadership

We’ve been focusing our efforts on Indigenous-led conservation and restoration because it is both the right and best thing to do, advancing reconciliation while safeguarding carbon stocks and boasting higher levels of biodiversity and reversing wildlife loss.

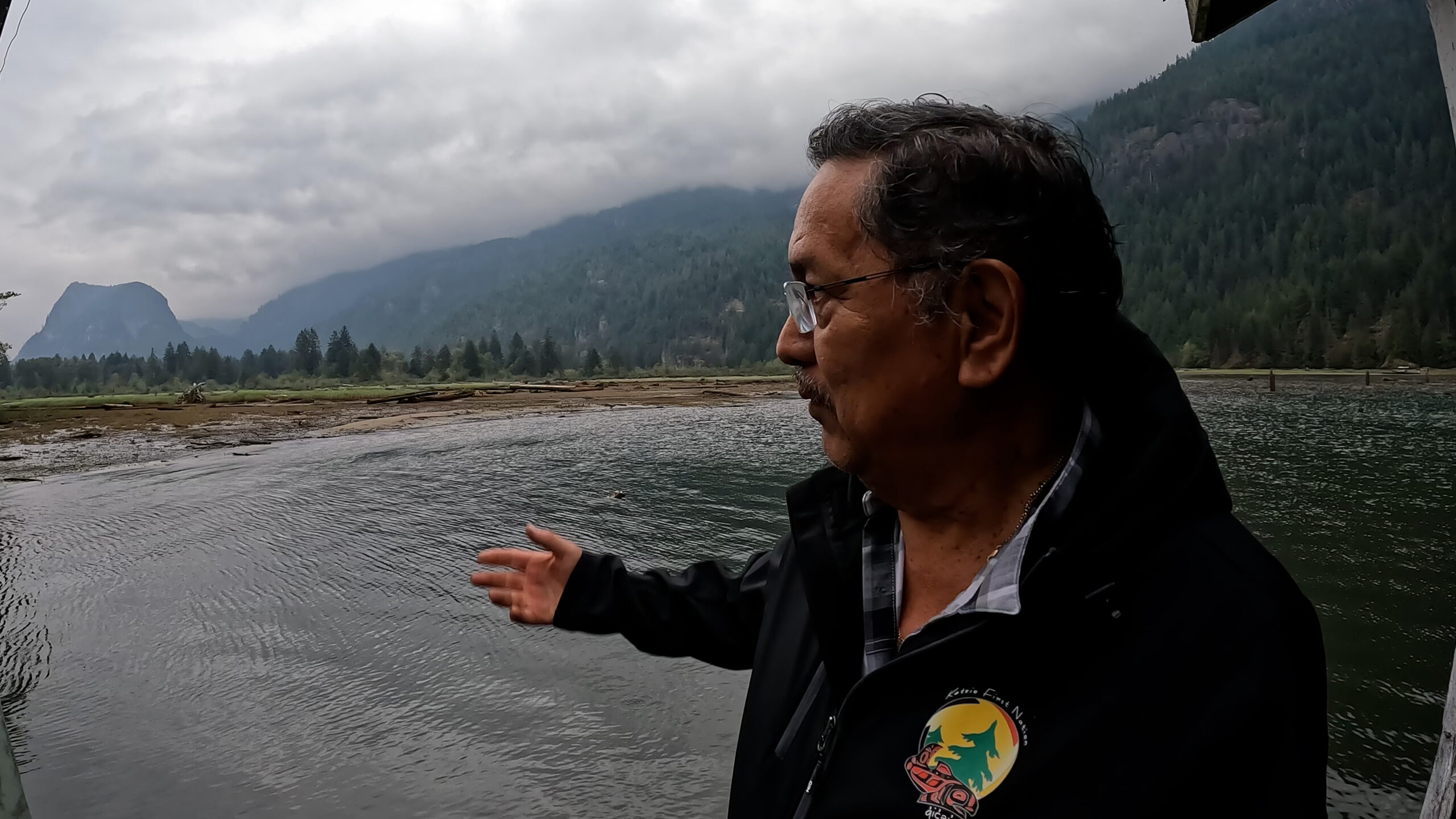

Our work with Secwepemcúl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society in central B.C., for instance, resulted in 250,000 trees planted this year — ramping up to a half-million next season and 10 million year by 2030 — while our vital salmon habitat restoration efforts supporting Katzie First Nation in B.C.’s Upper Pitt watershed saw even more spawning success.

Governments have been busy announcing major Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area initiatives, including an historic Tripartite Nature Agreement and an action plan for a future Great Bear Sea MPA Network. (Many nations aren’t waiting, instead declaring their own IPCAs to steward their traditional territories.)

In the Arctic, we saw continued progress on creating the nearly 90,000-square-kilometre Aqviqtuuq Inuit Protected and Conserved Area, with Guardians now monitoring the land and water, members of Taloyoak Umarulirijigut Association meeting with federal ministers (including at WWF-Canada events) and an Aqvituuq case study in our commissioned report by the Smart Prosperity Institute on Nunavut’s Blue Conservation Economy. We also supported knowledge-sharing exchanges between communities in the Kitikmeot region and another season of Arctic Species Conservation Fund research projects, including a month-long research expedition studying climate impacts on narwhal and beluga.

Science and Technology

Our work at WWF-Canada is fuelled by science, and in 2023, we released important studies providing a crucial foundation for on-the-ground conservation.

Our Restoring Lost Habitats in Canada analysis noted that 50 million hectares of non-urban land in Canada have been “converted” for human uses such as roads, energy infrastructure and, predominantly, agricultural lands. It then identified 3.9 million hectares — primarily in southern Ontario and Quebec and southern Manitoba — that have the greatest potential to provide maximum carbon storage and habitat for wildlife if restored to their natural states.

Other publications ranged from a milestone collaborative report on coastal blue carbon ecosystems to a study projecting LNG shipping traffic in the Great Bear Sea would cause unsustainable losses to fin whale and humpback populations from ship strikes, making a peer-reviewed case for mitigation measures before it’s too late.

We also concluded our Nature x Carbon Tech Challenge, awarding $300,000 to three recipients for their cost-effective, cutting-edge and user-friendly carbon measurement technologies which will now be implemented in the field with community partners like SRSS.

And we continued using AI, satellite telemetry, eDNA, machine learning, LiDAR and other advanced tech to better protect caribou, polar bears and other at-risk species.

Water Wins

There was a lot of motion on ocean conservation in 2023, beginning with February’s IMPAC5 international oceans summit in Vancouver where progress was announced on several First Nations-led marine protected areas. The feds also finally committed to an MPA “protection standard” (looks like your 23,000 “No Dumping” letters worked!), which restricts ship waste and prohibits bottom trawling, mining and oil and gas activities in MPAs. Plus, they de facto banned deep seabed mining and pledged to protect underwater seamounts.

We also got Chevron Canada and ExxonMobil to voluntarily surrender 20 “sleeper” oil and gas exploration permits following our co-lawsuits with David Suzuki Foundation. There was also an historic UN High Seas Treaty that will create MPAs in formerly lawless international waters for the very first time.

And we didn’t forget about freshwater. The government put money into creating an independent Canada Water Agency to address our much-needed freshwater protection and restoration requirements and, during COP28, joined more than 30 other countries in the Freshwater Challenge, the world’s largest initiative to restore degraded rivers, lakes and wetlands and protect vital freshwater ecosystems.

Terrestrial Triumphs

Our multi-million-dollar Nature and Climate Grant Program, presented in partnership with Aviva Canada, continued to direct funding towards a half-dozen restoration projects across Canada. The Comox Valley Project Watershed Society, K’o´moks First Nation and City of Courtenay are working to unpave a former sawmill site on Vancouver Island. The Kennebecasis Watershed Restoration Committee in Sussex, N.B. planted 12,000 shrubs to stabilize degraded riverbanks, reduce flooding and increase carbon sequestration. The Nottawasaga Valley Conservation Authority worked with landowners on wetland, river, forest and native grassland habitat restoration in rural Ontario.

Friends of the Rouge worked to protect, restore and regenerate the forest, stream, wetland and meadow habitats east of Toronto. The Redd Fish Restoration Society worked with local First Nations to restore mountain slopes surrounding Tofino, B.C., which had been stripped of trees and shrubs by intensive logging, leading to damaging landslides.

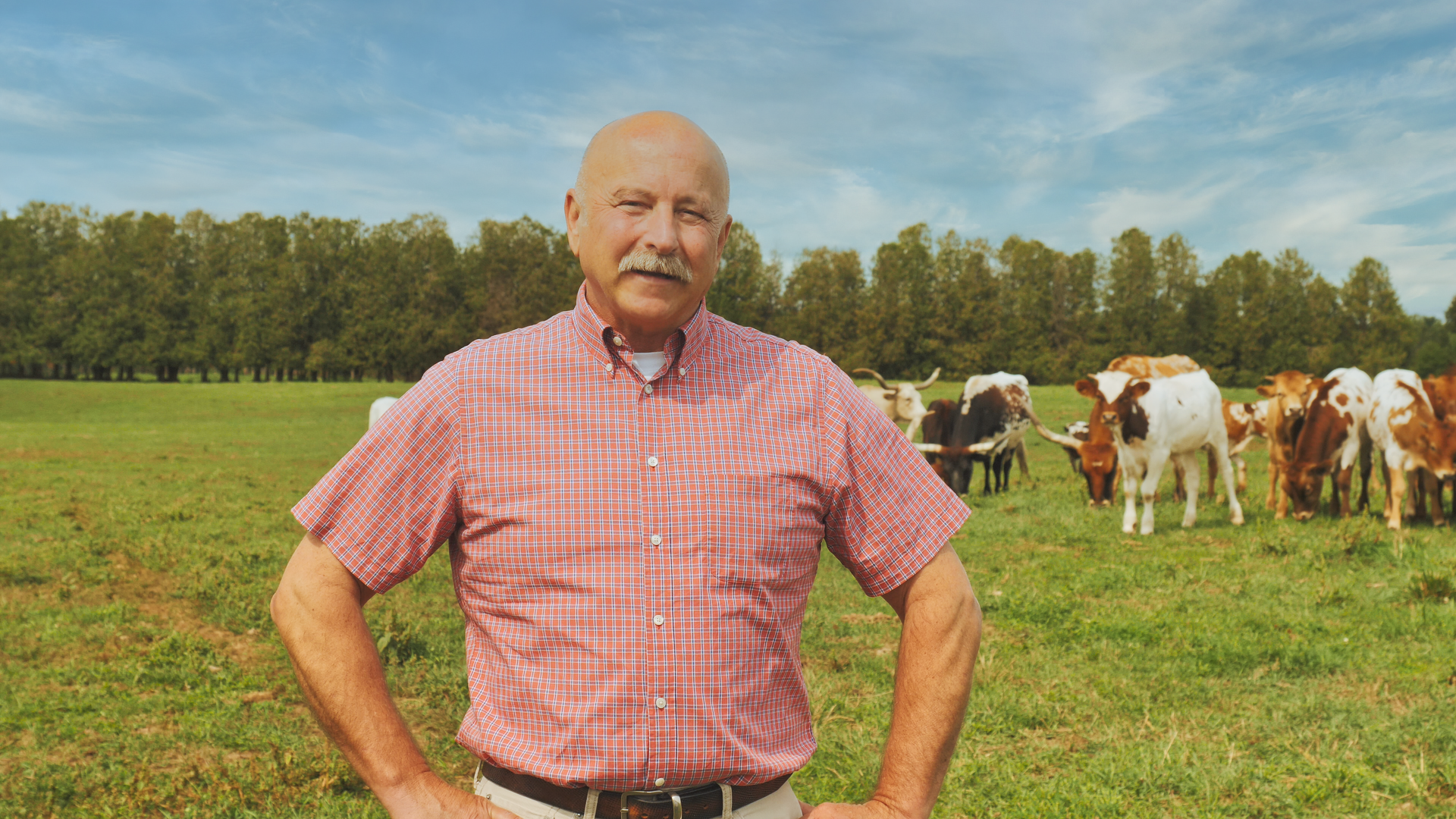

And ALUS sowed change in Ontario and Quebec by working with farmers and ranchers in six different sites to create “multifunctional farms” that also offer habitat and ecosystem services through actions such as reforesting field edges with native trees and reintroducing tallgrass prairies and open-water wetlands. They also adjusted their agricultural practices to protect wildlife and improve carbon sequestration in soil.

Community

Our supporters really came through in 2023, signing up for our new re:grow national native-planting program and planting In the Zone-tagged native plants — helping to create habitat for wildlife at their homes. Our Living Planet @ Campus program celebrated its 100th Living Planet Leader and we were able to fund 45 student restoration projects through our Living Planet @ School Go Wild Grants program.

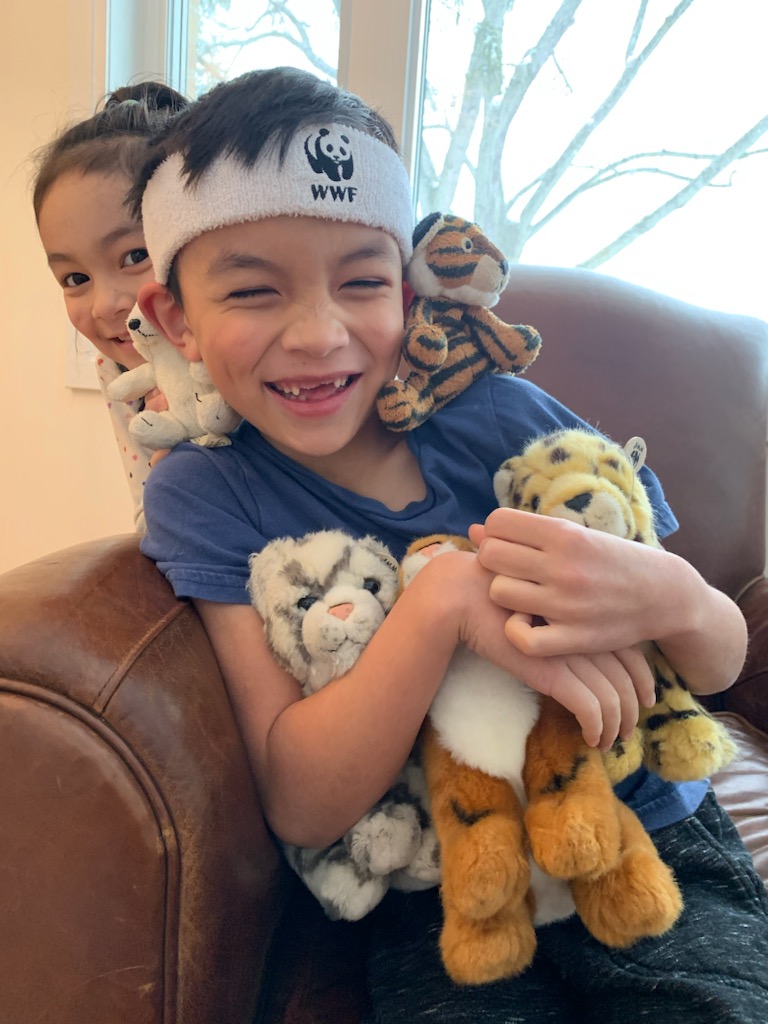

You really came through when it came to giving, returning to our first post-pandemic CN Tower Climb for Nature in droves to raise an incredible $1.36 million for conservation. And our partnership with ECHOage topped $1 million dollars fundraised at 7,000 birthday parties and other special occasions to, in the words of 8-year-old Lachlan, “help fight climate change and save the animals!”

Thank you all so much — and we promise to continue fighting for our planet in 2024.