Can we return tigers to the grassland, forest and mangrove habitats they lived in long ago?

About two centuries ago, tigers roamed most parts of Asia — from the shores of the Black Sea to the tips of the Korean Peninsula. But as habitat was lost to human development and tigers were lost to poaching and the illegal wildlife trade, the roar faded.

Even now, as tiger numbers rise after centuries of decline, the different places on Earth where tigers can be found continue to shrink. Today, the world’s most threatened big cat is restricted to less than five per cent of its historic range, scattered across just 10 countries.

Simply protecting these remaining fragments of habitat won’t be enough. But can we really return tigers to the grasslands, mangrove swamps and forests they once lived long ago?

WWF’s study, Restoring Asia’s Roar: Opportunities for Tigers Recovery Across their Historic Range, shows that, despite the odds, there is significant potential to recover the tiger’s threatened range.

Factoring in human impacts and settlements, the study identified 1.7 million square kilometres of additional habitat across 15 countries where tigers could return. This is nearly double the size of the current tiger range! This includes habitat in all ten current tiger range countries and countries where tigers vanished years ago.

In Nepal, there are still vast swaths of potential habitat available for tigers. What’s more, much of this potential habitat is found within 100 kilometres of the current tiger population. This suggests that significant range recovery could be driven by the natural dispersal of tigers into new territories — if only we give them the chance.

There is recent evidence that such dispersal events are already taking place. For example, in the Himalayan foothills of Bhutan and eastern Nepal, cameras captured an image of a tiger at 3,165 metres — the highest documented altitude for tigers in Nepal and it happened just 250 kilometres east of the country’s known tiger range.

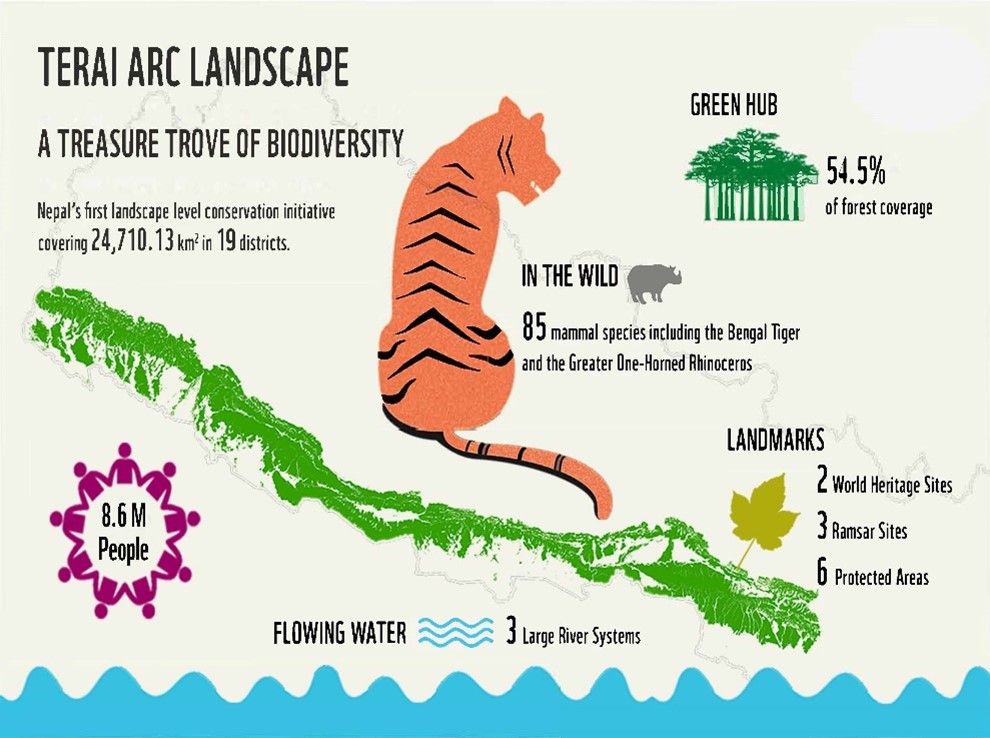

The Terai Arc Landscape — which stretches across Nepal’s southern border with India and connects 16 protected areas — was a major factor in the country’s doubling of wild tigers as these natural movement corridors allowed tigers to roam more freely and safely across their range.

It was recently recognized by the UN Environment Program and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations as the “World Restoration Flagship.” This designation is given to the first, best or most promising examples of long-term ecosystem restoration around the world.

Plus, restoring and protecting tiger habitats can help boost global efforts to halt nature loss. Tiger habitats overlap nine globally important watersheds, which supply water to as many as 830 million people, and forest landscapes protected for tigers serve as critical carbon sinks probing when we restore the roar, we protect so much more.

With human-tiger conflict quickly becoming an urgent threat to the survival of tigers, partnering with local communities to secure and increase the protection, restoration and connection of such areas is essential to sustaining tiger recovery in the long-term.

Bringing back the tiger’s roar is not just a bold and ambitious vision for Asia’s most iconic and endangered big cat — it’s also possible if we look beyond where tigers live now and focus our attention on the habitats tigers can and need to be now and far into the future.

Nepal has plenty of room for more tigers, but we need to secure these landscapes.