Nunavut’s native plants are among the planet’s toughest

Here today, gone tomorrow: the growing season in Nunavut is but a fleeting 50 to 60-day window. Add conditions that can be cold, dry or windy even during that stretch and you can see how the largest territory in Canada poses unique challenges for its native plants.

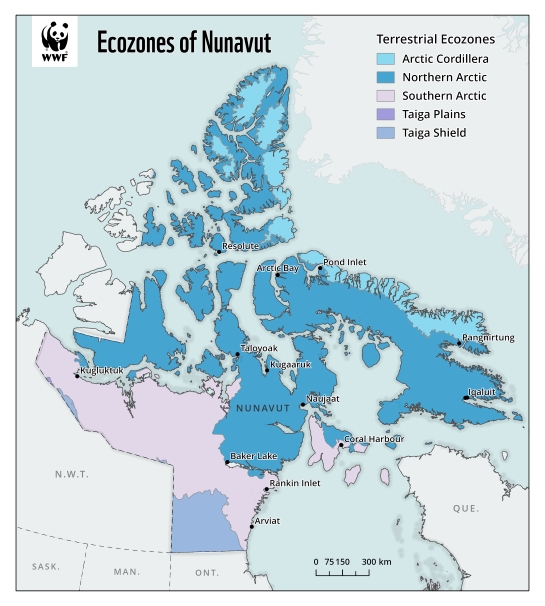

Nunavut’s five terrestrial ecozones extend from the mountains and glaciers of the Arctic Cordillera and plains and plateaus of the Northern Arctic to the Taiga Shield’s open forests, lakes and wetlands.

Across these environments are more than 1,000 species of plants. Many have short life cycles to make the most of the brief growing season and are perennial, storing energy in roots over winter to get a head start on next year’s growth.

While parts of Nunavut reach temperatures in the 20s and 30s Celsius at the height of summer, the season’s average maximum overall is only around 12 degrees C. To avoid the cold, plants often establish in microclimates that are warmer than surrounding air with structures like hairy stems and leaves or cup-shaped flowers to trap and hold warm air close to the plant.

To withstand wind, many species grow in low cushion shapes that allow gusts to pass over top. Downward-facing flowers allow insect pollinators to reach pollen and nectar without flying higher where wind is stronger. And where insect pollination isn’t possible, plants can reproduce by other means such as wind pollination (wind blows pollen from one plant to another) or self-pollination (fertilizing themselves, no mates or pollinators needed).

Precipitation in Nunavut tends to be scarce, but areas of snow cover and spring snowmelt do help plants to cope in places that are otherwise dry.

These hardy native plants provide a strong foundation for Nunavut’s land-based food webs, which sustain people as well as wildlife like lemmings, ptarmigan, barren-ground caribou, snowy owls, Arctic foxes and more.

Here are just a few examples of Nunavut’s formidable flora. (To learn about native plants in some other regions in Canada, check out our posts on B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick).

Purple saxifrage / Aupilattunnguat

Purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia) blooms early and prolifically, ushering in spring with bright five-petaled, pink-purple flowers. Well adapted to wind and cold, this species grows in wide cushions less than five centimetres tall. The stems are hairy and encircled by small leaves to trap a layer of warm air near the plant.

Traditional uses of purple saxifrage include eating the flowers and making tea from the leaves.

Given its cheerful appearance, hardiness and usefulness, it’s no surprise that the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut chose purple saxifrage for the territory’s floral emblem.

Growing Tips

Purple saxifrage is native to parts of all provinces and territories in Canada except Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and P.E.I, and to other countries surrounding the North Pole. Habitats include Arctic tundra, alpine habitats, wetlands and shorelines. In theory, purple saxifrage can grow well in a rock garden. But with seeds not widely available, visiting these plants in nature might be the easiest way to enjoy them.

Benefits for Wildlife

Caribou forage on purple saxifrage. Bumble bees, moths, butterflies and flies visit for pollen or nectar and pollinate the flowers. However, these insects aren’t active when conditions are particularly harsh. To get around this, the plant can also self-pollinate.

Blueberry / qiigutangingnaat

This shrub (Vaccinium uliginosum) stands less than 15 centimetres tall and belongs to the same genus as the cultivated highbush and lowbush blueberries that you may be used to if you live farther south. Like those other blueberries, qiigutangingnaat, the Inuktitut name, are popular to pick and eat. Berry-picking season gets many Nunavummiut out on the land to gather this species, along with other favourites like paungaaq (crowberry, Empetrum nigrum) and aqpik (cloudberry, Rubus chamaemorus).

In addition to eating them fresh, Inuit have traditionally preserved blueberries in oil or fat and both Inuit and Dene have used the leaves to make tea.

This plant’s flowers look like small pink and white bells. Spaces in between the oval-shaped leaves maximize the amount of sunlight that reaches them. In fall, the leaves turn from blue-green to red and fall off the plant.

Growing Tips

This blueberry is native to parts of every province and territory in Canada as well as Alaska and northern parts of Europe and Asia. Habitats include tundra, bogs, sedge meadows, forested areas, shorelines and rocky outcrops at a range of altitudes and with varying moisture conditions.

If this species isn’t already growing near you and you have suitable habitat, check for it at nurseries or explore the many other edible berry-producing plants in the Vaccinium genus to find one that’s native to your area and well suited to your growing conditions.

Benefits for Wildlife

Insects are attracted to blueberry flowers. Pollination by bumble bees and flies helps the plants produce bountiful, plump berries. However, the flowers can also self-pollinate if insects are unavailable.

Ptarmigan, spruce grouse, mice, voles, snowshoe hares, caribou, black bears and grizzly bears eat the leaves and/or berries. Animals that eat the fruit spread the seeds when they defecate.

Arctic willow / Suputiit, suputiksaliit, uqaujait

Unlike towering willows elsewhere in Canada, Arctic willow (Salix arctica) is a dwarf shrub that grows as high as a metre at most. In comparison, the black willow (Salix nigra) native to Ontario and Quebec is the largest willow in North America, growing up to 12 metres high.

Male and female Arctic willow plants produce catkins, elongated flower clusters which can look hairy or spiky. Later, fluffy seeds emerge and are dispersed by wind. Inuit harvest this fluff to make a wick for the qulliq, a traditional stone lamp that burns oil from seal or whale blubber. Other plants such as cotton grasses (Eriophorum spp.) are used as qulliq wicks as well.

Growing Tips

In addition to Nunavut, Arctic willow is found in Northwest Territories, Yukon, B.C., Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and other northern countries around the globe. They grow on tundra, rocky ridges, cliffs and mountains as well as bogs, meadows and gravelly or sandy areas.

Arctic willow is hard to find commercially. Try looking for one of the other dozens of willows native to Canada at local nurseries. Note that the “dwarf Arctic willows” or “blue Arctic willows” on offer are often the introduced species purple willow (Salix purpurea) and not the native Salix arctica.

Benefits for Wildlife

Muskoxen, Arctic hares and collared lemmings eat Arctic willow as do caterpillars of the dingy fritillary butterfly and the Arctic woolly-bear moth. Polar bumble bees also visit these willows for their nectar and pollen and to pollinate the flowers.

Help restore native plant life across Canada

Learn more about native plants in Canada and how you can help restore wildlife habitats by growing them. Visit wwf.ca/regrow.