Grey water dumping threatens ocean health and people

Chronic industrial pollution and climate change are transforming our oceans and helping drive a global biodiversity crisis. Among the many sources of ocean pollution, none are as prevalent — or as solvable — as “grey water” from ships.

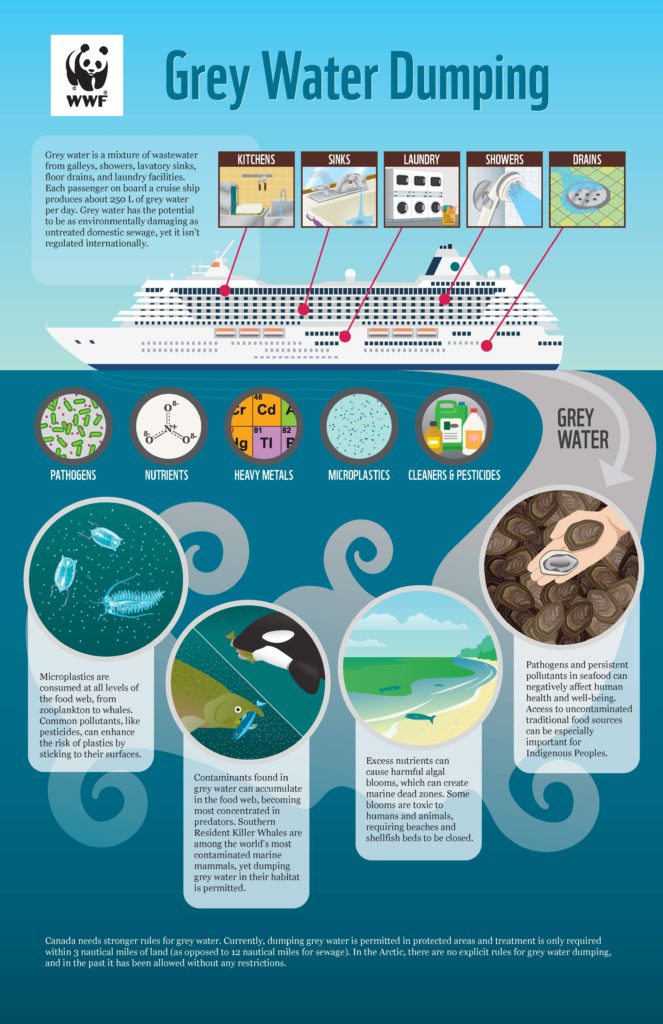

It’s a mix of wastewater from cooking, cleaning and laundry as well as sinks, floor drains and showers. It’s also a vector for pathogenic viruses and bacteria, among other hazardous substances like toxic cleaners, pesticides, heavy metals, nutrients and plastics.

So why isn’t Canada doing more to protect us from grey water?

Without intervention, contaminated seafood, fish deaths, beach closures and disappearing wildlife may increasingly become the new norm. Canada has a responsibility to safeguard oceans, human health and local economies on all three coasts by ensuring regulations keep up with industry growth and technological advances.

Low-hanging fruit

Grey water from commercial vessels — including cruise ships, by far the largest contributor — has the potential to be as environmentally damaging to surface waters as untreated domestic sewage. More effective solutions, such as Advanced Wastewater Treatment Systems and compliance monitoring, currently exist but haven’t been implemented due to regulatory stagnation.

But shipping pollution hasn’t stalled instead, it mirrors the sector’s dramatic growth in recent decades. According to a recent study produced by Vard Marine Inc. for WWF, cargo vessels produce 125 litres of grey water per day per person while cruise ships produce more than double that. For an average-sized cruise ship, that’s roughly 750,000 litres of grey water daily. In 2017, ships were estimated to have dumped 1.5 billion litres of grey water off the BC Coast — 90 per cent from cruise ships. A separate study, also produced by Vard on behalf of WWF, projected that the amount of untreated grey water dumped in Canadian Arctic waters could double to an estimated 60 million litres by 2035 if left unregulated.

A multitude of microbes

Grey water is rife with microorganisms originating from food and the human body. The US Environmental Protection Agency has found in some instances that grey water has higher concentrations of fecal coliform than domestic sewage, which are associated with the pathogens that cause salmonella, typhoid, cholera and dysentery. Noroviruses, rotaviruses, and adenoviruses — pathogens responsible for fevers, coughs, sore throats, diarrhea, vomiting and pink eye — are also present in grey water. Exposure can occur through activities like swimming or consuming contaminated shellfish.

Dead fish, dead dogs, sick people

Key nutrients in grey water can fuel harmful algal blooms (HABs), which cause mass ecosystem dysfunction by producing toxins, blocking sunlight and clogging fish gills. After the bloom dies, the process of decomposition consumes locally available oxygen, creating marine dead zones. Human exposure to toxic HABs can cause ear, eye, nose, skin and throat irritation, as well as respiratory distress, abdominal pain, diarrhea, liver and kidney damage, vomiting, seizures and paralysis. Wildlife and domestic animals are similarly affected. Notably, exposure to toxic HABs has been linked to instances of dog mortality.

We don’t want that in our food

Grey water includes substances with known toxic and carcinogenic properties, some of which can cause DNA damage and negative birth outcomes in people and wildlife. Yet, millions of litres of grey water containing metals, macro- and microplastics, rodenticides, insecticides, personal-care products and cleaners are dumped in Canada’s territorial waters every day.

Some, like metals and microplastics, accumulate in the marine food web and can be passed on to humans. For instance, the annual dietary exposure for European shellfish consumers is estimated to be 11,000 microplastics per year. Microplastics attract other persistent contaminants present in the water such as metals, PCBs, PAHs and pesticides such as DDT.

Contaminants present in grey water can exacerbate pre-existing risks. For instance, a single Pacific oyster can already contain more cadmium than a pack of cigarettes and the average albacore tuna contains about 40 per cent more mercury than the average thermometer. In short, more contaminants in our oceans translates into more contaminants in our bodies.

Alaska’s bad neighbour?

Despite these dangers, grey water isn’t regulated internationally. Canada regulates grey water in its territorial waters differently above and below 60°N. In the south, ships only need to treat grey water with a marine sanitation device (MSD) when dumping within three nautical miles of land (outside of that, they can legally dump it untreated).

Thing is, MSDs are designed for treating sewage — not grey water. They’re also ineffective, even for sewage. Separate studies conducted in China and the Netherlands found that MSDs fail to treat sewage to minimum standards 81 per cent to 97 per cent of the time, respectively.

In the Arctic, Transport Canada (TC) turns a blind eye to grey water by neither certifying nor approving grey water treatment systems for use in waters above 60°N but TC also doesn’t expressly prohibit grey water dumping in the Arctic either. This encourages shipowners to dump grey water, which is either untreated or treated to unknown standards. After all, tanks are only so large and holding untreated greywater is unsafe: fecal coliform can multiply 10-100x during the first 24-48 hours in a holding tank.

In comparison, Alaska is a global leader for ships’ grey water treatment, monitoring and discharge standards.

What comes next?

In the immediate future, any bridge loans, as the federal government announced recently, for the cruise industry should be part of a Green Recovery Plan and be tied to new mandatory minimum standards.

More broadly, MSDs should be phased out in favour of Advanced Wastewater Treatment Systems (AWTS) that eliminate excess nutrients, microorganisms and persistent organic pollutants; compliance monitoring should be conducted and enforced to ensure the continued effectiveness of on-board grey water treatment systems; all grey water should be treated, regardless of distance from shore; and it shouldn’t be dumped in marine protected areas treated or untreated to safeguard community food security and ocean health.