After the fire: How technology can drive successful restoration

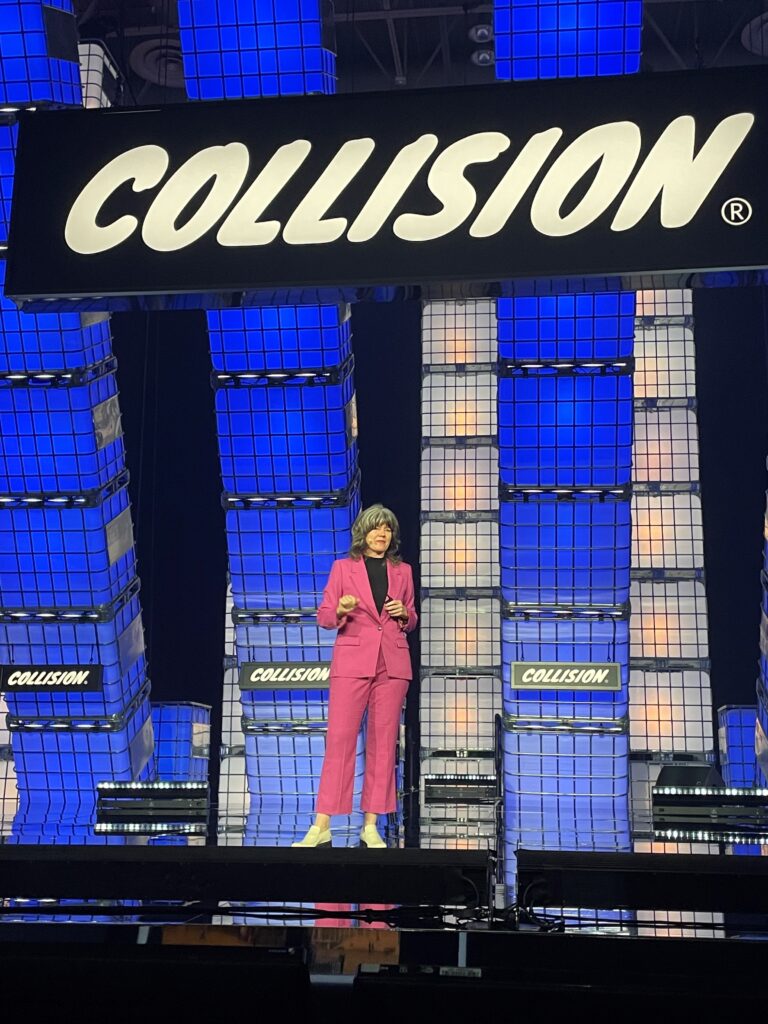

In the midst of Canada’s worst wildfire season in recorded history, it’s time to re-evaluate how we deal with the restoration of forest ecosystems. Megan Leslie, WWF-Canada’s president & CEO, delivered a keynote address at the recent Collision tech conference in Toronto about how Indigenous-led conservation and technology can help build resilience in the face of climate change.

“One thing about me is I’m an incredible optimist, and that’s been a pretty hard position to hold on to lately. As wildfires burn across Canada, we’re watching trees and vegetation disappear. Trees and vegetation that are important habitat for wildlife and that also hold significant amounts of carbon in their roots, stems and soils.

And all of it is — literally — going up in smoke. As surreal images of smoky, orangey-lit cities were broadcast around the world, people were losing their homes and facing uncertainty. And while many species have adapted to either run away from or burrow beneath wildfires, the intensity of today’s fires are making it hard for them to escape.

And then there’s the impact on the climate. The trees and soils of forests hold a huge amount of stored carbon that’s been absorbed by photosynthesis from the atmosphere. When those forests burn, that carbon is released back into the atmosphere, further amplifying global warming through positive feedback loops.

Why is this all happening?

Of course, we know that wildfires can be a natural part of ecosystem activity but let me assure you that this frequency and severity of fire is not natural.

Forests are more vulnerable to fires than they once were. And it’s all connected — climate change has altered rainfall cycles and created hotter and drier conditions in some regions while milder winters allow new invasive insects to spread, creating vast stands of dead trees that act as kindling for wildfires. On top of that, humans have weakened the resilience of forests to fire because we’re managing them, principally for yield.

What’s missing in that picture is all the other plants: the understory, the wildflowers and shrubs and the diversity of species. They’re not truly forests. Forests are rich, messy, complex, thriving ecosystems.

In many cases we can’t see the forest for the trees because trees are all we planted. Resilience, wildlife and climate change are left out of the equation.

We can do better than this

We have to do better than this.

So let’s talk about what we can do to recover after these terrible fires and also prevent this magnitude of fire from happening again because it’s possible to do both at the same time!

READ MORE:

Wildfires, wildlife and what we can do

Here’s why Indigenous-led wildfire restoration works

The Reforesting of Elephant Hill

First, we must do absolutely everything we can to address climate change and avoid the worst of its impacts. This means reducing human-caused greenhouse gas emissions through decarbonization.

And since ecosystems store carbon, it also means avoiding the release of carbon from nature by preventing the damage and destruction of carbon-rich ecosystems like our peatlands and forests.

We have to protect these places not only from development, but also protect them from future fires. That means we need to change how we manage forests to promote resilience and finally, it means increasing the sequestration of carbon in nature by restoring lands already converted or damaged.

And this is the solution I want to explore with you, because technology has so much potential to transform the way we do this work.

Let me tell you about the Secwepemcùl’ecw Restoration and Stewardship Society’s efforts to reforest Elephant Hill.

This is a nearly 200,000-hectare area of their territory near Kamloops B.C. that burned for three months during 2017. The aftermath of the fire left community members reeling. Many lost their homes, and the surrounding landscapes changed forever with widespread post-fire erosion and landslides that further threatened already damaged salmon habitat.

Instead of reforesting using the standard approach of modern forestry that prioritizes coniferous trees with higher economic value for logging the community set their own approach, an approach grounded in their own values and Indigenous knowledge that prioritizes resiliency and biodiversity.

It meant also planting deciduous trees, which happen to be more fire resistant! It meant prioritizing planting an understory below the canopy. It also meant measuring and monitoring the carbon left in their landscapes (and how it is changing with time) so that they could validate their approach and attract new investors to support their restoration efforts.

And this is where technology comes in. Historically it’s been extremely costly and time consuming to measure and monitor carbon in nature, making it very difficult to do a proper “before and after” assessment and impossible to determine how carbon levels change in reaction to conservation efforts.

We needed an inexpensive and efficient approach to measuring carbon in nature that was also user-friendly. So WWF-Canada created the Nature x Carbon Tech Challenge, a challenge to catalyze tools for nature based climate solutions and now one of the final award recipients is working with the SRSS to help validate their efforts.

Innovatree Carbon Group Ltd has developed a software that relies on LiDAR data and machine learning to calculate carbon found in forest biomass. This technology produces information that can be scaled down to the individual tree.

And this level of detailed information is important because there’s a ton of variability when it comes to carbon sequestration.

Picture that messy forest again. I mean, trees grow at different rates and even trees that are side by side may have different levels of shade and moisture. A more detailed analysis provides a greater level of accuracy and precision. It can also tell us if these trees are surviving following restoration.

Now you might be wondering why we need to bother with reforestation. Why forests aren’t regenerating on their own after fire?

Some of us learned school about how the heat of fire forces open conifer cones and then the seeds inside are distributed. Well, in some of the fires we’re seeing today, conditions are so hot that they are searing the soil and cones, leaving nothing to grow. Reforestation help is needed, and tech is being deployed to make it faster, easier and cheaper.

There is some dark stuff happening out there, but I have hope. A lot of it. And that’s because we have solutions and opportunities. There are incredible examples out there of how technology developed for one purpose can be adapted to serve a different, yet critical, purpose for nature, wildlife and climate.

Technology is a cornerstone of conservation, helping us to scale our impact beyond our wildest dreams. Technology is making conservation better.

And as we can see in interior B.C., technology, combined with Indigenous knowledge is changing how we can work to restore nature after these fires burn out.”