Translating snow and ice science into policy

Earth’s cryosphere is on the brink of a preventable disaster. Rising temperatures from carbon emissions are pushing communities closer to the limits of their ability to adapt, forcing mountain regions to cope with water shortages and coastal areas to confront sea-level rise caused by melting polar ice sheets.

As Amy Imdieke, global outreach director for the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, writes, the State of the Cryosphere 2023 report clearly lays out why we must keep the global temperature rise below 1.5°C.

At the UN Climate Change Conference in December, scientists shared the 2023 report on the state of the cryosphere with government leaders, ministers and climate negotiators working on the frontlines of global policy-making. The report outlines the latest snow and ice science and emphasizes the need for urgent fossil fuel reductions to prevent the worst-case scenarios for future generations. Its message this year was simple: even a 2°C temperature rise is too high to prevent devastating global impacts from cryosphere loss.

“We have time, but not much time,” wrote Chilean President Gabriel Boric and Iceland’s Prime Minister, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, in the report’s preface. “Past alerts are today’s shocking facts. Present warnings will be tomorrow’s cascading disasters, both within and from the global cryosphere.”

Five key cryosphere dynamics

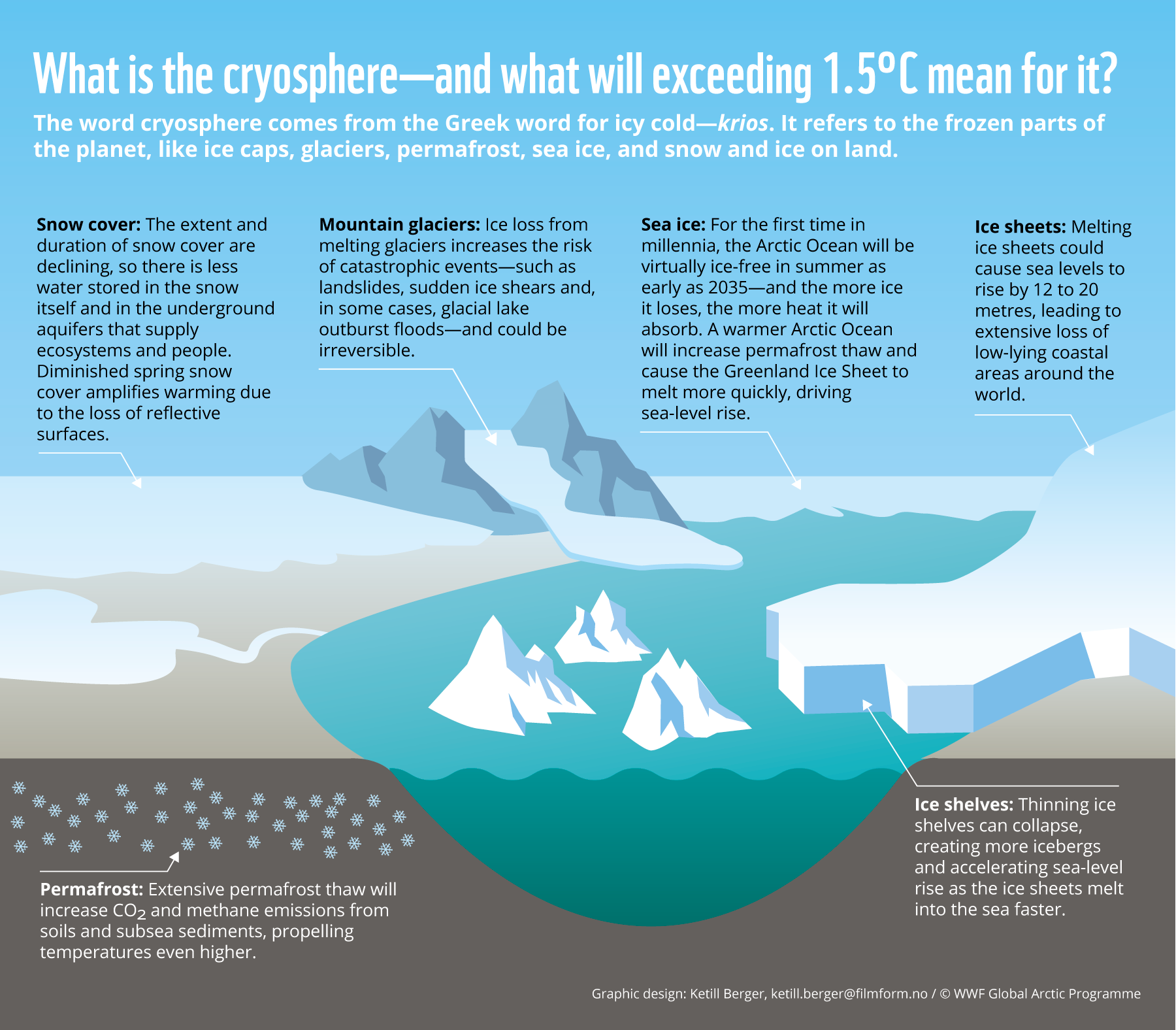

The report focuses on five dynamics that are highly relevant to national and global climate policy: permafrost, sea ice, ice sheets and sea-level rise, mountain glaciers and snow, and polar ocean acidification, warming and freshening. The first such report was released just ahead of the landmark climate conference in 2015, with scientists urging greater ambition as the Paris Agreement was concluded.

Cryosphere science is evolving at an incredibly rapid pace. Not only do new findings each year yield worrying observations, such as those concerning recent trends in Antarctic sea ice, but they paint an increasingly detailed picture of what Earth’s future will look like under different emissions scenarios due to cryosphere loss.

As a result, the state of the cryosphere report is now released annually before the UN Climate Change Conference each fall. The report is coordinated by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative and reviewed by an international team of more than 60 cryosphere scientists, including many Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change authors. As experts in their fields, they take the pulse of the cryosphere, translating the latest science into terms that can be understood by government and business leaders, negotiators and the general public. The report outlines how cryosphere loss will change the world if we do not reduce carbon emissions with enough ambition and urgency.

Arctic and Antarctic research have flourished in recent years, with satellite observations, expeditions and collaborative papers exploring even the most remote regions of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets — two regions of key concern to low-lying nations far away from the poles.

Irreversible change

Most recently, researchers discovered that West Antarctica and Greenland will cross irreversible thresholds if global temperatures climb by more than 1.8°C, even temporarily. Such a rise would commit these ice sheets to increased ice loss and accelerate global sea-level rise for several centuries. Only the very lowest greenhouse gas emissions scenario — in which temperatures peak around a 1.6°C rise and level off below a 1.5°C rise by the end of the century — avoids long-term acceleration of sea-level rise from the Earth’s two great ice sheets.

The latest science is clear: ice sheets have the potential to spur a greater and faster sea-level rise at lower temperatures than previously thought. Most seriously, these changes will be essentially permanent, even with an eventual return to lower temperatures.

Academic work on mountain glaciers has also advanced. More accurate models are forecasting greater ice loss at today’s temperatures and indicating that it will take centuries or even millennia for this ice to return, once lost. A high-emissions scenario will result in total or near-total glacier loss in the mid and low latitudes by 2100, including a loss of up to 80 percent among glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalaya.

Cascading impacts

Disappearing glaciers strain seasonal water supplies for high mountain and downstream communities alike, with impacts cascading through agriculture and food security to global trade.

These cryosphere changes are not locked away in some distant future. They are already the reality for millions of people, from those living on unstable permafrost soils in the Arctic to those living in the foothills of the Himalayas and along the coastlines of small island states.

Extreme events are increasing in frequency and severity across Antarctica, including heatwaves, all-time low sea ice conditions, ice shelf collapse, and species population crashes. These trends will continue unless radical actions are taken to reduce fossil fuel emissions to net zero by 2050.

Yet the State of the Cryosphere 2023 report still offers a strong message of hope: cryosphere loss is still preventable. What happens next depends on the actions we take to reduce carbon emissions today. At its core, 1.5°C is a window into what our world could look like for generations to come — and it will be worse if we take too long to act.

This article originally appeared in the WWF Global Arctic Programme magazine, The Circle.