Will we ever be prepared for the inevitable Arctic oil spills?

The exploitation of rich oil and gas reserves in the pristine Arctic has been controversial for decades. Debates have raged between environmentalists and big oil companies, between national interests and the wider concerns of the United Nations Environment Programme.

To date, many multinationals have shied away from exploiting these resources — but as Simon Boxall writes, with scarcity and demand growing in tandem, there are increasing pressures on the region.

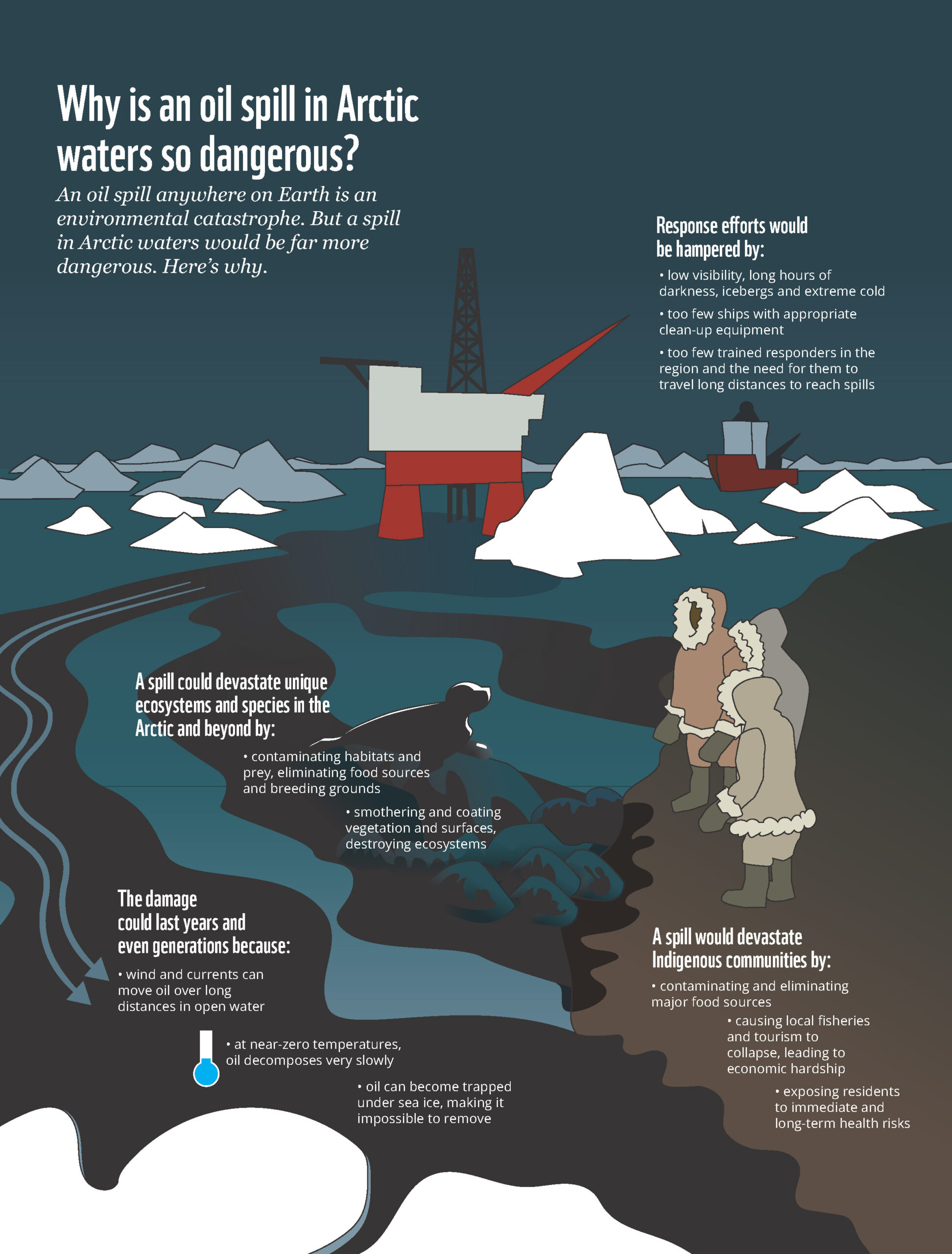

The Arctic’s inhospitable climate and extensive ice sheet have long presented an operational block to oil and gas extraction. The irony is that the region has warmed — and the sea ice retreated— because of our extensive use of fossil fuels. Setting the engineering challenges aside, the biggest concern is that a spill in the Arctic — and there will be one — will be very different from others that have occurred in more temperate regions.

I have come to realize, with experience, that there are three rules for an oil spill:

- Don’t have one.

- If that fails, then stem the spill immediately and contain and collect as much of the leaked oil as possible in the early stages.

- Having done the best you can with 2, do nothing more, apart from learning from the experience to improve your future chances of 1.

Let’s start with 1. Increased tanker safety and better wellhead design have reduced the number of incidents. But in the push toward more extreme environments, we become more vulnerable to those environments — Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico (the largest marine oil spill in history) being a good example.

Arctic operations will have to deal with both extreme storms and extensive ice flows. These can damage production platforms as well as the vessels and pipelines used to transport the oil and gas.

Help is not at hand

This brings us to 2: Deepwater Horizon teams were on site within hours, thanks to readily available ships and the ability to fly thousands of tonnes of specialized equipment to the site. But the Arctic is remote — very remote. I was once hit by a big storm in the middle of the Greenland Sea. A concerned colleague asked: If we should sink, how long would it be before a helicopter could reach us? The answer: we were beyond the range of any helicopter, and the nearest ship was about two days’ sail away.

Similarly, the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound was south of the Arctic Circle, yet it still took a couple of days before equipment started to arrive—a critical delay in containment and recovery.

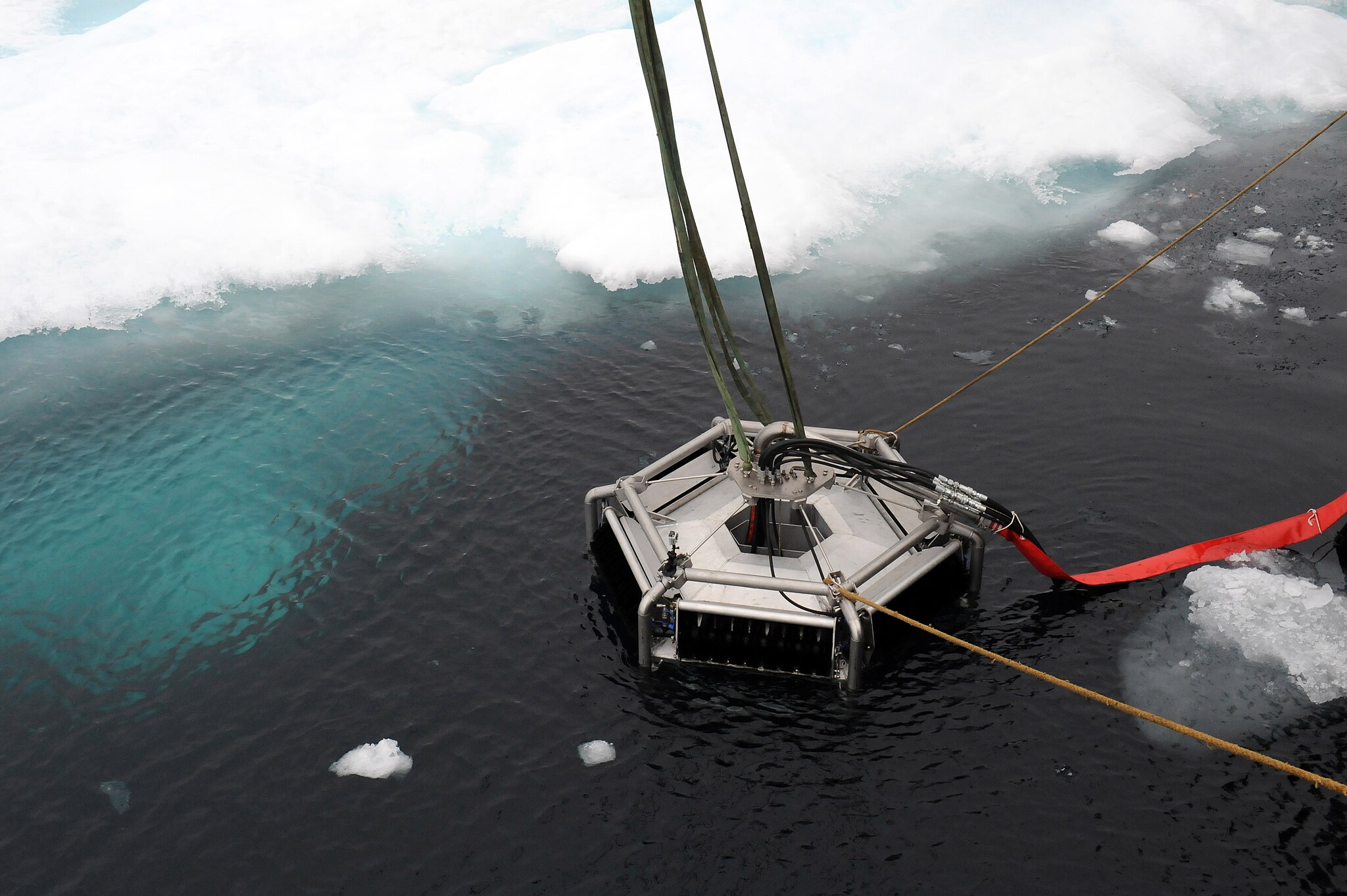

A further complication in the Arctic is the sea ice. All of the equipment that has been developed to date for oil spill containment and removal or dispersal assume a clear sea surface, but we have yet to figure out what to do about a spill under the sea ice. I fear the answer will be nothing.

But the biggest problem in the Arctic is actually number 3. The ocean is full of oil-eating microbes that grow substantially when oil is present. Oil has seeped from fissures in the seafloor for millions of years, dispersed over large areas and broken down in a matter of weeks. In the open ocean, away from sensitive environments, the best option for a moderate spill is to do nothing: nature kicks in. In fact, many consider that the efforts to clean up after the Exxon Valdez spill caused more harm than good. The region’s small population grew by several thousand clean-up staff, with all their associated requirements for power, transport, sewerage and housing.

Let’s not add to the stress

Studies have shown that over a period of five years, oil spill areas left untreated have experienced the same rate of recovery as many of the cleaned areas, or better. Microbes work well in tropical, temperate and even cold areas like Prince William Sound. However, the high Arctic is another matter. We are putting our oil-covered sea into a very cold fridge, preventing the microbes from doing their work.

I was on Svalbard once and came across an old, abandoned Swedish coastal research station that had last been used in the 1970s. There were two abandoned heating oil drums. The drums were completely rusted away, but two perfect moulds of oil left behind showed no sign of breaking down. There is ongoing research that aims to engineer oil-mopping microbes that can survive these extremely cold environments, but even then, we would have to contend with the unforeseen impacts of these cold-resistant microbes.

The Arctic is a unique biosphere that is already under severe stress. Increasing ocean acidity, rapidly warming seas, and the loss of much summer sea ice are affecting all forms of life, from the smallest pteropods (sea butterflies) to the largest polar bears and bowhead whales.

The inevitable oil contamination will add a further and substantive strain on this fragile ecosystem, and we have yet to find solutions to deal with such an environmental disaster.

Simon Boxall is a sea-going oceanographer who studies a range of marine topics, including oil spill detection, at the University of Southampton School of Ocean and Earth Science.

Why is an oil spill in Arctic waters so dangerous?

This article originally appeared in WWF Arctic’s latest issue of The Circle: “Leave it in the Ground.“