We need to talk about shipping

Addressing the shipping sector’s climate impacts is a large part of our success in tackling the climate crisis

Look around and you will realize that almost everything we buy — in fact, 90 per cent — reaches us via ship. Even the device you’re using to read this was likely shipped from overseas. Shipping is an essential service that plays a vital role in global trade.

But why, then, is such a service — one with a substantial impact on our lives — almost invisible to us?

It’s similar to how many of us don’t read food labels: when we’re looking at something in front of us, we rarely look behind to see how it got there.

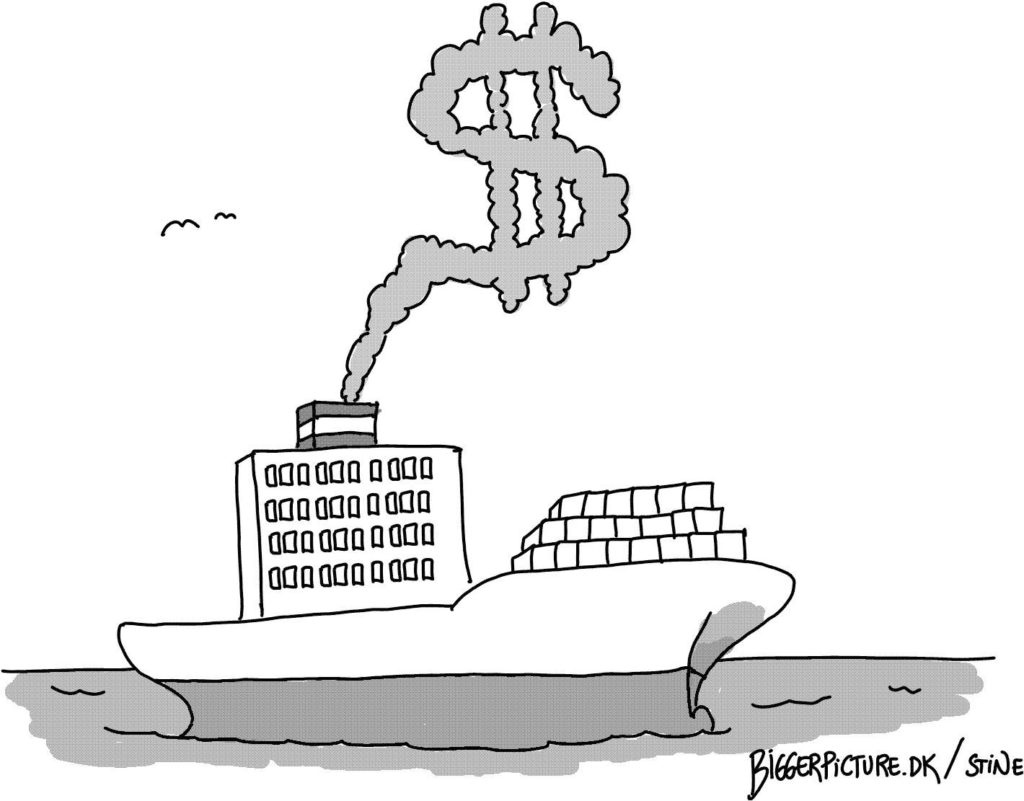

But it’s time for this to change. We need to talk about shipping and its increasing environmental footprint.

Is the greenest mass transport really green?

Trading at an international scale would not be financially feasible were it not for shipping. Trucks and planes consume more fuel and emit far more greenhouse gases (GHGs) than vessels. The shipping industry is more efficient than other mass transport. But this doesn’t mean that the industry is green.

The shipping industry’s sheer size (and its expected growth—CO2 emissions from maritime sources are projected to increase anywhere from 50 to 250 per cent in the period up to 2050) means that its emissions matter. Indeed, if the shipping sector were a country, it would rank sixth on a global GHG polluters scale.

The climate crisis and the international maritime industry

In 2018, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a United Nations agency responsible for regulating shipping, adopted strategies for reducing GHG emissions from international shipping by at least half by 2050 (relative to 2008 levels).

The IMO’s achievement in setting emissions reduction targets for an entire industry is remarkable. But it can’t end there. The climate target for the shipping sector is insufficient to keep temperature increases below 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.

IMO strategies are due for revision by 2023, and they must include more ambitious climate targets. We need a shipping industry that reaches zero-emissions by 2050.

What about Canadian shipping?

The Government of Canada implemented a federal carbon pollution pricing system under the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act in 2019. This system applies a federal fuel charge according to their carbon emissions when burned and is currently levied at $30 per tonne of emissions. The charge covers marine fuels used in domestic voyages between two points in the same jurisdiction where the federal fuel charge applies. Provinces and territories that have established their own carbon pollution pricing systems that meet the federal benchmark may also cover marine fuels.

So far so good, right? Not really. Applying the federal carbon polluting pricing system to marine fuels is a puzzle with many exceptions and concessions. In addition, provinces and territories can apply the federal system in whole or in part, choosing to include (or not include) the shipping industry.

No plan, no gain

Norway and the UK have established an ambitious domestic climate target of zero emissions by 2050. And as the world moves to address the climate crisis, Canada should not be left behind.

The Canadian government needs to provide a framework that includes incentives and mandates for the shipping industry to take actions towards decarbonization. An action plan needs to include concrete targets, measures/monitoring, timelines and budget.

With such a framework in place, the marine industry will be able to acquire experience and expertise and be in a good position to deal with the shipping sector’s restructure. A Canadian maritime plan needs to incorporate consultation with Indigenous peoples and strong policies and actions that address the risks facing people, infrastructure, economies and ecosystems in the transition to a clean marine industry.

Doing nothing is not an option

Ongoing emissions of GHGs and black carbon, a sooty black material emitted from carbon-based fuels, will continue to intensify the climate emergency. This will lead to higher global average temperature and a cascade of related impacts, including increases in severe weather and rising sea levels. And the cost of action will likely rise in the future with the probability of misallocation of investment and infrastructure as a result of the cascading effects of climate change.

All hands on deck!

In the transition to a clean shipping industry, Canada has a constitutional, legal, and international obligation to consult and collaborate with Indigenous peoples. The long-term success of Canada’s transition to a clean marine sector and a low-carbon economy will only be possible with the collaboration of provinces and territories, Indigenous peoples, municipalities, businesses and other stakeholders. These changes in the marine sector will mirror behavioural changes to a low-GHG economy at all levels of Canadian society. The shipping industry has the potential to help lead the way or risk being left behind.