Fieldnotes: Why you otter be less salty this winter

Fieldnotes is WWF-Canada’s newsletter about our science-based work finding solutions in the face of an unprecedented crisis in climate change and wildlife loss. Please click here to subscribe and get future issues emailed direct to your inbox.

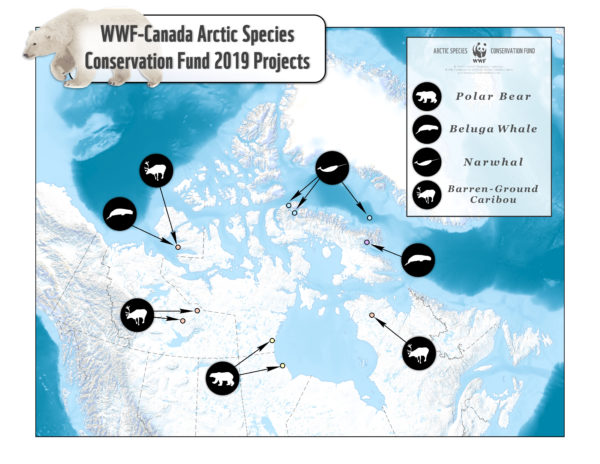

We distributed $250,000 for research projects to protect Arctic wildlife amid the climate crisis

Using satellites and drones to safeguard beluga. Employing Inuit knowledge to prevent caribou extinction. Measuring climate and shipping impacts on narwhal. Reducing human-polar bear conflicts. These are just a few research projects that received $250,000 from this year’s Arctic Species Conservation Fund — the fifth exciting field season for this WWF-Canada project.

Established in 2015, our fund has already allocated $650,000 to support more than 50 high-quality research and stewardship projects across Nunavut, Quebec, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. By partnering with university researchers, government scientists and local Indigenous organizations, this work helps protect iconic and at-risk Arctic species like beluga, bowhead whales, narwhal, barren-ground caribou, polar bears and walrus.

Our ten 2019–2020 projects are largely focused around the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on the rapidly warming North.

We have several narwhal projects, for instance, looking at ways the changing climate is affecting these beloved marine mammals. One is evaluating if we’re protecting the right narwhal over-wintering habitat by studying the Disko Fan Conservation Area in Baffin Bay. In a warming Arctic ecosystem, we expect changes in wildlife home ranges and habits, so as these shifts occur, we must evaluate existing protected areas to see if they’re accomplishing what they were designated to do.

Another project is studying the stress levels of narwhal exposed to industrial development by looking at the impact of increasing iron-ore ships in Eclipse Sound. This will be vital information for protecting marine species as the melting ice increases shipping traffic across the Arctic. And our Narwhal Camp project is now in data–analysis mode, identifying migration routes and core winter and summer habitats as well as investigating how the warming climate and increased ship presence is affecting the whales.

These projects also combine traditional Inuit knowledge with leading-edge technology. To help the recovery efforts of the isolated Cumberland Sound beluga, currently listed under the Species at Risk Act, researchers are using satellite data and aerial drones to assess the critical habitat and nursery areas of one of Canada’s most threatened beluga populations.

Barren-ground caribou face even more dire circumstances. One ASCF project is looking into the impacts of mining infrastructure — monitoring stress levels and migration — while others are working closely with Inuit and First Nation groups to leverage their Indigenous knowledge and expertise to conserve the Bathurst and George River herds, which have declined by 98 per cent and 99 per cent, respectively. (Yes, you read those numbers correctly. An upcoming all-caribou edition of Fieldnotes will look deeper into these dramatic declines and efforts to reverse them.)

The Arctic is heating up faster than almost anywhere else on Earth, and this scientific research will help the communities and species of the north weather these dramatic climatic changes as best they can.

Tracking problem polar bears to protect people and bears

Human-polar bear conflict rates are at an all-time high in the western Hudson Bay region of Nunavut, with severe concerns for community safety. One of the biggest causes is climate change — declining sea ice is bringing this polar bear subpopulation into hamlets and hunting camps in search of food, endangering residents and bears alike. So, WWF-Canada’s Arctic Species Conservation Fund is supporting several initiatives to mitigate this.

WWF has been a longtime partner in the world’s most comprehensive long-term polar bear study, which occurs in the Churchill region. This year, the project continues using ear-tag radio transmitters to focus on the movements of polar bears that have caused problems in Churchill to better understand which types of bears are prone to conflict.

Another ASCF-funded study is using camera traps to figure out what contributes to conflict between polar bears and people. These cameras will identify bears that are causing problems around the community of Churchill, MB and Arviat, NU and determine when and why polar bears approach communities and camps, and what is driving these dangerous interactions.

Q&A: Why you otter be less salty this winter

Southern Ontario waterways are showing dangerously high road salt levels. Although it can keep public areas safe during icy winters, overuse has become a critical threat to Ontario’s freshwater and wildlife. We spoke with freshwater specialist Anthony Merante to learn how we can be less salty this winter.

Why is road salt bad for our environment?

Road salt contains chloride, which is toxic to our environment. The salt spread on our pavement doesn’t disappear with the snow and ice. Instead, it seeps into soil, flows from roads and parking lots into sewers, and makes its way into our creeks, rivers and wetlands.

Some urban creeks in Southern Ontario are as salty as oceans in the winter and spring! Excessive road salt use creates an uninhabitable environment for vegetation and freshwater wildlife.

How is road salt affecting freshwater ecosystems and wildlife?

Salt is changing the chemistry of freshwater ecosystems — fish, frogs and mussels aren’t adapted to salty conditions. It affects their breathing, reproduction and overall health. It’s like how people are adapted to a certain percentage of oxygen. If that changes, it starts to affect our health — it’s the same thing with freshwater wildlife and their ecosystem.

Wetland plants and trees are also affected by high chloride levels because our soils are saturated with salt. Since salt has been accumulating in our waterways and soils, it threatens species year-round.

What is WWF-Canada doing to address this issue?

We’re working with various stakeholders like property management companies, environmental NGOs and universities to understand the root of over-salting. Last year, we worked with Ryerson University who led a pilot on reducing road salt use on their campus during the winter season. We pushed for leading practices that balance public safety and environmental health with property management companies.

We also developed the Great Lakes Chloride Summer Hot Spot Map to inform policy recommendations to the Ontario government like establishing a Provincial Water Quality Objective to address species at risk that are susceptible to chloride levels.

How can we be less salty during the winter?

We need to find a balance between public safety and environmental safety. Road salt is only effective between 0 and –10 degrees, so if it’s too cold, it does nothing but contaminate the environment. Salt is only for ice, not snow removal, and can be used sparingly — about 2.5 tablespoons can clear a square metre!

Shoveling your property and keeping drains clear can help prevent icy conditions, and clearing areas you use daily, like a walkway or driveway, is better than clearing your entire property. This automatically reduces the amount of road salt you’re using during the winter.

Meet a…Scientist

Martha Lenio, Specialist, Renewable Energy, Arctic

Based out of WWF-Canada’s Iqaluit office, Martha works to decrease diesel use in the North and develop strong relationships with communities by working on green energy projects that matter to them.

She has a BASc in Mechanical Engineering, a PhD in Photovoltaic Engineering, and has worked in sustainable building design, PV R&D, solar consulting, education, and is involved in numerous renewable energy non-profits and boards.

“I love working at WWF — my work helps communities in Nunavut transition away from fossil fuels, which ensures this unique area is protected for future generations.”