No, I don’t want no scrubbers

A scrubber on a ship leaves harmful discharge out at sea

As the shipping season opens in the north and vessel traffic increases along Canada’s coastline, TLC’s famous 90’s song, “No scrubs” resonates very well with current environmental issues caused by scrubbers.

© Ashley Cooper / Global Warming Images / WWF

Also known as Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems, scrubbers were designed to remove sulphur oxides from exhaust gases that are created as fuel is burned in marine engines. Sounds good, right? Not really. Unfortunately, most of the time scrubbers take what was an air pollution problem and turn it into an ocean pollution problem.

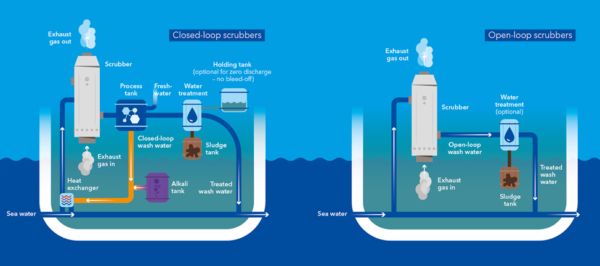

Here is what happens inside a scrubber

Before being released into the air, the ship’s gaseous emissions enter the scrubber and mix with the scrubbing material—this can be solid lime, seawater or freshwater with the addition of various chemicals. The scrubbing material is an alkaline solution, while the emissions are acidic. The scrubber neutralizes this acidic nature of the exhaust gases and removes pollutants such as sulphur. The treated exhaust is then released into the atmosphere, minus a portion of those harmful pollutants.

© DNV GL AS 2019

Herein Lies the Problem

Scrubbers are meant to function similarly to a catalytic converter, using a chemical process to treat and purify emissions. The source of those emissions on a ship is heavy fuel oil — the world’s dirtiest transportation fuel — that when burned, creates more particulate matter than other fuels. And that particulate matter is left in the scrubber fluid and not completely removed from the exhaust released into the atmosphere.

A big cruise ship on an average seven-day voyage can produce up to five tonnes of scrubber sludge and about 75,000 m3 of wash water. Those need to go somewhere. The scrubber sludge is stored on board the ship and disposed of at port. The scrubber wash water can be either stored on board the ship, which is what happens with so-called “closed-loop” scrubbers, or discharged immediately at sea, which is the case for the “open-loop” scrubbers that make up more than 80 per cent of installed or ordered scrubbers.

Even though the International Maritime Organization (IMO) accepts the use of scrubbers as a mechanism to reduce a vessel’s sulphur emissions, there is enough evidence showing that scrubbers are also associated with a range of marine environmental impacts:

- Scrubber effluent contains heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that, when accumulated in the environment, have carcinogenic effects, can cause mutations and impact marine life. This also affects human health as affected fish and crustaceans are consumed by coastal communities, such as across the Canadian Arctic, that rely on fishing as part of their diet.

- Scrubbers are not proven to be efficient in removing small particles such as sulfate particulates which contain sulphur. The small-scale particulates pose a significant risk on human health.

- Scrubber discharge causes immediate and focused environmental degradation due to the acidic character of the discharge, higher temperature compared to the surrounding water and the turbidity generated by the discharge.

© Andrew S. Wright / WWF-Canada

Scrubbers and the climate crisis

The use of scrubbers does not contribute to the transition to cleaner fuels. It allows operators to continue to run on heavy fuel oil. Beginning in January 2020, the IMO requires vessel operators to limit their fuel sulphur content to 0.5 per cent. They can do this in one of two ways: switch to a cleaner fuel or install a scrubber and demonstrate equivalent compliance.

Counter to the point of these regulations, the use of scrubbers can increase the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from ships by approximately two per cent per vessel because it takes more energy, and therefore fuel, to operate the scrubbers, including the pumps for collecting water from the ocean for scrubber fluid.

The shipping industry is already responsible for nearly three per cent of global CO2 emissions. By stalling the adoption of cleaner fuels, which is in effect what the use of scrubbers is doing, ships can continue to use heavy fuel oil that tends to produce higher amounts of black carbon than any other marine fuel. When emitted in the Arctic, black carbon increases the region’s surface temperature five times more than when emitted elsewhere because it coats the white surface of Arctic ice with soot, absorbing more sunlight and creating a feedback loop.

So, what can be done?

Several coastal states and ports around the world have adopted more stringent local regulations to restrict or completely prohibit the discharge of wash water from scrubbers. This means ships with scrubbers installed are forced to hold their discharge or use cleaner fuel when navigating these waters.

Canada needs to take bold action by not allowing scrubbers as an equivalent compliance mechanism for reducing fuel sulphur content, meaning a shift to cleaner marine fuel. More broadly, Canada needs a plan and strategy to phase out hazardous and polluting ship fuels, like heavy fuel oil. Decarbonizing the shipping industry and addressing the climate crisis can’t be achieved by prolonging the use of some of the world’s worst shipping fuels.

Scrubbers not only delay the reality of zero-emission shipping but pollute the ocean and harm a food source for many coastal communities.