Wildlife is dying due to road salt, and it must stop

It’s white and granular and gets spread heavily every winter. We see it pouring onto highways and staining our boots. It’s familiar. And it’s toxic.

It’s road salt, and it’s having a devastating impact on the freshwater ecosystems of the Great Lakes.

Road salt, the most common being sodium chloride, dissolves easily in water and flows from roads and parking lots into the sewers, and then into our creeks, wetlands, rivers and lakes. In the winter and spring in the Great Lakes region, salt levels in groundwater and surface water regularly reach levels that are dangerous for wildlife.

WWF-Canada’s recent Watershed Reports showed very high threats from pollution to the Great Lakes watershed. In this region, with its dense network of pavement and people, excessive use of salt in winter is responsible for the toxic conditions damaging aquatic life.

Freshwater fish can’t survive in water that’s too salty, and salty water kills eggs and larvae of wildlife such as mussels. Frogs and turtles die when there’s too much salt in lakes and rivers.

Disturbingly, there are reports that salt-water species such as blue crabs introduced into Ontario lakes and rivers are able to survive because of all the salt we’ve dumped into the environment.

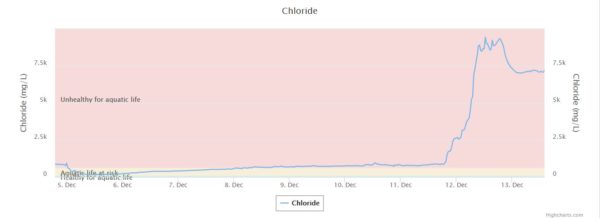

This graphic shows the measurement of Cooksville Creek in Mississauga, Ont., after the first significant snowfall in the Greater Toronto Area on Dec. 11, 2017. Road salt was spread during the wintry conditions and the effects on the creek were evident within hours. The deeper pink background area shows where salt reaches unhealthy levels for aquatic life. Because wintry conditions have continued since that day in mid-December, salt levels have remained very high and unsafe for wildlife in the creek for weeks now.

Road salt also ends up in our drinking water. Although Health Canada does not set a maximum concentration for chloride in drinking water, in some places in Ontario, such as Waterloo Region, salt concentrations can reach the level where tap water tastes salty.

World Wildlife Fund Canada is working to achieve a measurable reduction in road-salt use in Ontario over the next three years to improve the health of our freshwater ecosystems. To achieve this, we are:

- Partnering with businesses to reduce salt on their properties. Seventy per cent of road salt contamination in the Great Lakes watershed comes from private property, often large parking lots such as the ones around big-box stores. We’re partnering with property-management groups and creating tools to help them reduce their salt use this winter.

- Encouraging training and certification. We’re working with the Smart About Salt Council in Ontario to promote certification for those who salt roads and parking lots. Through collaborations with Landscape Ontario, we are engaging contractors to reduce the salt they spread. Using more salt isn’t better or safer, and education will help balance public safety with environmental concerns.

- Working for policy change. We’re advocating for a policy change that will require commercial enterprises and municipalities in Ontario that use road salt to undergo training and certification. With our partners, including the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority, we’re advocating for an Ontario-wide road-salt reduction strategy.

The salt spread on our roads and parking lots doesn’t melt away with the snow: It accumulates in our creeks, rivers and other water systems. We must recognize the damage it does to freshwater wildlife, and take steps to stop the harm.